Advertisement

The New Health Care

There are reasons to question an expert panel’s recommendations for children.

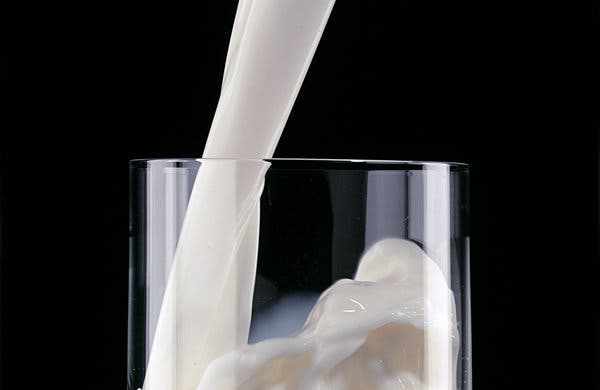

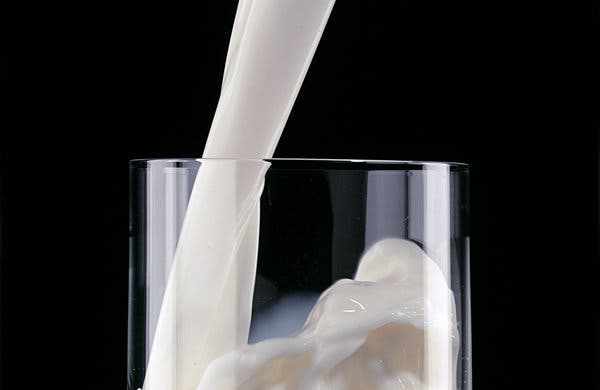

Is there such a thing as a healthful beverage?

In truth, there’s not much of a health case to drink any beverage other than water after the age of 2 — despite the marketing and advertising you might have seen on the benefits of things like dairy milk, plant-based milks, juices and more.

All other mammals consume only two liquids over the course of their lives: breast milk and water. The evidence for telling humans that some beverages are necessary and that others should be avoided isn’t nearly as clear as many believe.

Last year, a group of leading health organizations released recommendations on what children should drink. They convened a panel and a scientific advisory committee. They pored over documents, studies and reports from all over the world.

The undertaking was about as thorough as it could be. Yet the recommendations they released are still somewhat disputed.

For children above the age of 1, dairy milk is “recommended,” although the fat content and amount changes with age. Juice should be limited, the panel says. Pretty much everything else except water should be “avoided.” This includes all plant-based milks, unless necessary because of allergies. This also includes “toddler milk,” which has increased rapidly in popularity (it contains mostly powdered milk, corn syrup and vegetable oil).

Before going any further, let’s acknowledge where there is consensus. Human infants, like all mammals, depend on milk for sustenance at the beginning of life. Breastfeeding (human milk) is almost always recommended, as well as baby formula until 1 year of age if breastfeeding is not feasible. Most experts also think that children should continue to be breastfed or transition to whole cow’s milk until they’re 2. The fat is believed to aid in brain development.

It’s at that point that things get tricky.

There’s very little high-quality evidence, and no comparable mammalian example, to argue for the specialness of cow’s milk after this period. Arguments that it’s good for you because it has protein and other vitamins and minerals could be made about many, many other foods (but those foods don’t receive such official recommendations of support).

The recommendation that we limit juice, and not just avoid it, is also somewhat questionable. The argument for juice is that while we’d prefer that children eat fruits and vegetables, some just won’t. In that case, the experts argue that 100 percent fruit juice “may be an important way to meet these recommendations.”

But juice is not healthful. It’s full of sugar. A 12-ounce glass of apple juice has the same amount as a can of soda (grape juice has even more). It’s also a processed food. It contains no fiber and does nothing to sate you. It’s empty calories. Studies show that adults who eat an apple before a meal consume fewer calories during that meal; drinking a glass of juice instead has much less of an effect on calorie consumption.

Oddly, the recommendations take a much stronger stance against plant-based milks, like almond milk or soy milk. Those should be “avoided” for children, not limited. Why? Because, as the authors of the recommendation note, in studies of their nutritional content they come up short compared with dairy milk.

It’s true that, with the exception of soy milk, plant-based milks have significantly less protein than cow’s milk. It’s also true that while some plant-based milks are fortified with calcium or vitamin D, it’s not clear that these are absorbed as well from other milks as they are from cow’s milk. But does that matter?

The authors cite two studies that show the “negative” impact of plant milk in children. The first was a cross-sectional study of children in Canada, and it found that children who exclusively drank noncow’s milk were more likely to have low vitamin D levels than those who only drank cow’s milk (11 percent versus 4.7 percent).

But only 5 percent of children drank exclusively noncow’s milk, and it’s very possible that there are confounding factors in their diet that might lead to this result. It’s also unclear if this low vitamin D level had any health implications.

The second study reviewed the literature and found 30 cases of clinical conditions associated with exclusive consumption of plant-based milks. First, this is essentially a collection of anecdotes. Second, almost all cases occurred in the first year of life, when children shouldn’t be consuming any milk except human breast milk. Even cow’s milk isn’t recommended there.

Of course, none of this should be taken as an argument that plant-based milks are superior to cow’s milk. Regardless of the hype (there’s usually plenty of that), they’re no more healthy or special than any other beverage.

I can’t imagine eating cereal without milk. But both are optional, and once you get to optional, it doesn’t really matter which milk you pick. Might children get a bit more protein from cow’s milk? Sure. But most children aren’t deficient in protein. Might children get a bit more vitamins and minerals from cow’s milk than fortified plant-based milk? Sure. But most children aren’t truly deficient in those in a way that would make a difference.

Moreover, too many children get more calories than they need, and cow’s milk has a lot more calories — and a lot more sugar — than plant-based milks.

When it comes to juice, it’s hard to argue that the empty calories are good for you at all. We’d never tolerate soda as being “healthy,” even if it came fortified with vitamins and minerals. It’s not that juice and soda are dangerous. They’re most likely fine in moderation, but we can allow them as a treat for children while still recognizing they’re not “recommended.”

The bottom line, as I’ve written before, is that every beverage other than water and breast milk might be treated the way alcohol is for adults — you can have it if you want it, but don’t be under the illusion that you need it.