In February, just before the COVID-19 outbreak upended life as we know it, I read . In the novel, a little-understood airborne virus hits a small university town, causing victims to fall into a deep, dream-filled sleep. Some of them recover. Some of them never wake up. It’s an eerily prescient look at how a government does and doesn’t respond to a disease in uncharted territory, and the ways people come together in its path. When the dreamers wake up, they’re not sure what, if any of it, existed beyond closed eyes.

Several weeks after I finished the book, Ahmaud Arbery was killed for jogging while Black. In March, COVID-19 first responder and aspiring nurse Breonna Taylor was murdered in her own bed by police serving a no-knock warrant to the wrong house. Two months later, our nation watched as Derek Chauvin held his knee on George Floyd’s neck, murdering him while three fellow police officers stood by. The past three weeks have seen national and international protests by Black folks, yes, but also a multiracial coalition of voices demanding change, as many non-Black Americans began waking up from our nation’s willful ignorance and perpetuating of anti-Black racism—our 400-year pandemic.

I don’t sleep well. I never have. I’m a clinically anxious person and that anxiety is often accompanied by insomnia. When I finally do fall asleep, I have nightmares as often as dreams. As a small child, I was convinced the KKK was going to show up at my parents’ house and hurt us. It was a nightmare, but I was wide awake to reality. I knew about the KKK as a small child even in sunny suburban California. Black children know about racism early. The world doesn’t give us a choice.

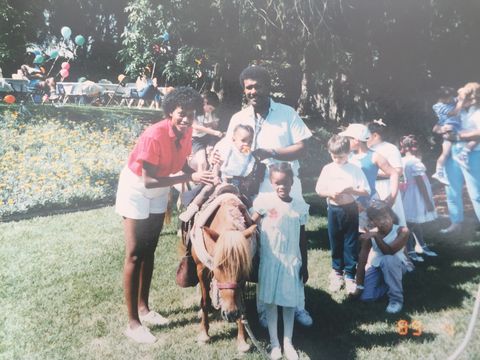

In the early ’80s, when my parents first moved in, the neighbors were suspicious. “Why do you need such a big house?” they asked, as though the idea of a newly married Black couple wanting space for their future kids to chase each other up and down the stairs and run around a beautiful backyard was an alien concept. We lived in that neighborhood because of my parents’ dreams for us: that we would be little-girl embodiments of MLK’s dream, Black girls who had sleepovers full of friends of all different colors, who were insulated from what years of systemic and institutional racism had done to many predominantly Black neighborhoods. That we would have the best education possible, and that we would be safe—playing, biking, jogging. My parents had so many dreams for us. The same dreams I’m sure Ahmaud Arbery’s parents had for him.

Once, when I was jogging in my neighborhood as a teenager, a car full of white men pulled up next to me and yelled, “Run, nigger, run!” Terrified doesn’t begin to describe my fear at that moment. It was the fear of my ancestors, the fear of my childhood nightmares, the fear of being a teenage girl sprinting from a car full of sneering men. I’m asthmatic, but I ran as hard as I could, petrified of what could happen if I stopped. I didn’t stop running until I reached the grounds of the school and church I’d grown up in (which, perhaps ironically, was itself predominantly white). Only there did I feel I could catch my breath.

Ahmaud Arbery did not get to catch his breath. George Floyd did not get to catch his breath. Philando Castile did not get to catch his breath. Sandra Bland never got to go home. Tony McDade never got to go home. Akai Gurley died in his own stairwell. Botham Jean died in his own apartment. Breonna Taylor died in her own bed. There are too many to list. Too many Black parents’ nightmares have come to life.

I am lucky in many ways. Amid so many nightmares, a dream of mine is coming true: I wrote a book and it’s getting published this August. All my parents’ sacrifices and dreams are coming to fruition. When I started writing my novel , I thought I was crafting a piece of historical fiction. In the book, a wealthy Black teenager named Ashley struggles to understand her place in the world against the backdrop of the 1992 Los Angeles riots. Through her eyes, we witness the impact of the Rodney King beating verdicts, and how Los Angeles was forced to reckon with the impact of not only police brutality, but also the anger, frustration, and hurt at years of economic and political disenfranchisement.

Little more than a decade and a half after the riots, those of us who were children in 1992 helped elect our first Black president. We celebrated in the streets and wept at the idea that we were bearing witness to Hope and Change. I cried the happiest of tears because my Black grandparents lived to see Obama’s victory. Many elated in sharing that victory with our elders, those whose bodies and lives had been so marred by the struggle for equality. But during the first year of Obama’s presidency, every time the words “Breaking News” came on my television screen, I stopped, terrified that “they” had hurt him or his beautiful family–the same “they” I’d feared as a child, the same “they” who tried to demonize and hang him in effigy. The same “they” who succeeded in dragging James Byrd behind a truck until he was decapitated in 1998, the summer before my sophomore year of high school, just a year before I took that nightmare jog.

Since that time, smartphones placed the internet and cameras at everyone’s fingertips, becoming the vehicle by which we share our lives, our joys, and our traumas. We have collectively borne witness to Black people dying at the hands of police, at the hands of wannabe vigilantes, at the hands of racists, all on our phones, our tablets, and our TV screens, over and over in the past decade. We are hurt. We are tired. We are angry at watching and living our parents’ nightmares.

I conceived of the short story that would become my novel in the Obama era. My book is nearing publication in the Trump era, just months before the next presidential election. I thought I was using the past to hold up a mirror to the present. I didn’t know the past would actually become the present. In 1965, during the Watts Riots, Chief William H. Parker of the LAPD compared rioters to a foreign enemy, the Viet Cong. In 1982, ten years before the L.A. Riots, Chief Daryl Gates—who would still be chief at the times of the riots—said, “Blacks might be more likely to die from chokeholds because their arteries do not open as fast as they do in normal people.” Normal People. In 2020, our current LAPD Police Chief, Michael Moore, said that George Floyd’s death, “is on [looters’] hands, as much as it is on those officers,” before quickly walking back his statement. Both my maternal grandparents passed away a few months after we watched the president say of the violent white supremacists in Charlottesville, “There were fine people on both sides.” I am so, so tired, but I can’t sleep.

I know my history—I lived and breathed April 1992 for several years, researching, watching, and re-living the events of the L.A. riots through my characters’ eyes. But as I watch these momentous protests unfold in 2020—multi-generational, multi-racial, and international coalitions demanding change—I, perhaps stupidly, can’t help but feel hopeful. I feel like maybe finally, as a country, many of us are finding ourselves on the same radio frequency, listening to Mister Señor Love Daddy in as he urges:

“Wake up! Wake up! Up you wake!”

The times of our ugliest racial strife have come right after our biggest successes. Emancipation gave way to the terror of post-Reconstruction. The Civil Rights Act gave way to the metaphorical and literal assassination of our Black leaders and the destruction of our inner cities. The hope of the Obama Era gave way to the hate of Unite the Right in Charlottesville. History has shown us time and again that the road ahead will not be easy, but not only is it the road worth taking, it is the only road if we are to ever actually uphold the promises of the Declaration of Independence—those venerated “truths” the Founding Fathers themselves failed to uphold.

There are promises to keep, and miles to go before we sleep.

Wake up. Up you wake.

Contributor Christina Hammonds Reed received her MFA in Film and Television Production from USC’s School of Cinematic Arts and was a Nicholl’s Fellowship Finalist.

This content is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page to help users provide their email addresses. You may be able to find more information about this and similar content at piano.io

This commenting section is created and maintained by a third party, and imported onto this page. You may be able to find more information on their web site.