Even as Washington legislators allocated tens of millions of dollars to boost care for severely troubled youth in the state’s child-welfare system this year, the numbers of those kids forced to sleep in hotel rooms or state offices hit record-breaking numbers, a forthcoming state report will show. While the COVID-19 pandemic has likely had some effect on that number, it doesn’t appear to be the primary cause, an InvestigateWest review of state data suggests.

Final figures are due out Tuesday, but preliminary numbers obtained by InvestigateWest show that the number of young people who had to stay overnight in hotels rose again in the last year. Even more striking: Caseworkers resorted far more often to putting children in government offices for the night when a suitable bed was unavailable.

In the year ending Aug. 31, caseworkers housed foster kids in state offices 284 times. That compares to just six times in the same period a year earlier. Prior to the latest numbers, the highest tally in the past six years was 47 in 2017.

“That’s just appalling,” said child-welfare advocate Dee Wilson, a critic of the state Department of Children, Youth and Families, the state child-welfare agency where he served as a regional executive from 1997 to 2004.

“I’m just trying to wrap my mind around it, really,” Wilson said after an InvestigateWest a reporter told him the new number of office overnights. “That just sounds like a system kind of falling apart.”

The young people in question are typically the hardest to place with foster parents in the state’s already-overburdened system. Many are deeply disturbed youths who can’t be placed in a regular foster family but instead require placement with a specially trained family or in a special group-home facility. They are young people who might spit at their caretakers, threaten them or even smear feces on the wall.

Appropriate placements for these difficult-to-manage young people have been in chronic short supply in Washington, which has resorted to sending some youths to out-of-state group homes. Capacity slipped again in July when a Seattle group-care home capable of caring for 18 children, the Spruce Street Inn, was cut off from state funding after failing to readmit kids who had tested positive for coronavirus.

All this ultimately affects public coffers. Experts say the more these kids are forced into untenable housing options such as motels or state offices, the worse they are likely to fare when they finally emerge from state care, rootless, as young adults. Foster youth in general, and these young people in particular, are far more likely than others to end up in jails, prisons and hospital emergency rooms, where taxpayers foot the bill.

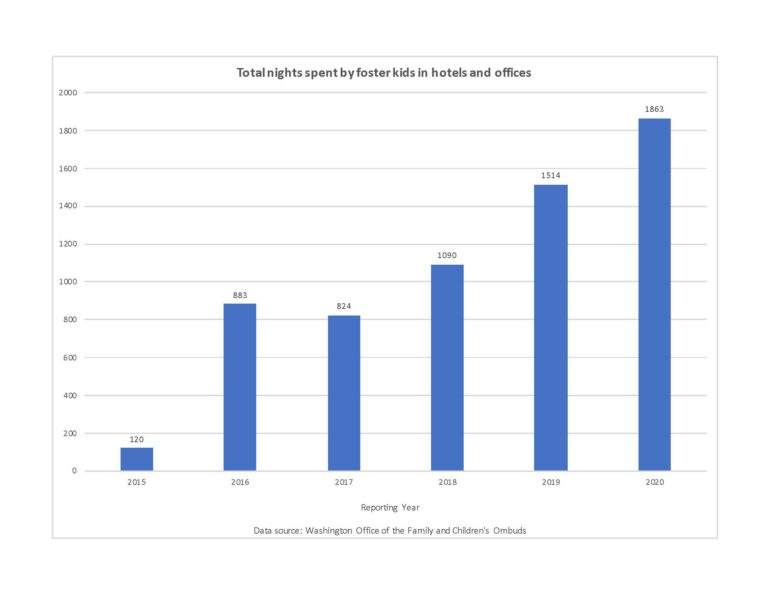

Kids stayed in state offices, hotels and a few other so-called “placement exceptions” for 1,863 nights in the latest reporting year, ending Aug. 31. That’s up from 1,514 in the previous year.

Chart shows number of nights spent in so-called “placement exceptions,” which almost always are hotels and state offices. (Data source: Washington State Office of the Family and Children’s Ombuds)

Ross Hunter, the former state legislator who heads DCYF, said his agency still is making changes to expand care authorized in the state budget that was approved by the Legislature last spring and went into effect July 1.

Hunter vowed to bring down the numbers of hotel and office stays next year, based on the new state funding and a raft of policy changes. He said $35 million-plus in new funding from the Legislature already has allowed the agency to start lining up new places to house the severely troubled youth.

In a telephone interview, Hunter declined to discuss the specifics of the DCYF office stays, citing federal healthcare privacy law. Regarding this year’s office stays, he said “it’s a problem with a very small set of children that I don’t want to talk more about because it starts to identify them.”

He added, “But we are well aware of this problem.”

Those 284 office overnights occurred among 43 children, according to figures obtained by InvestigateWest from the state.

According to agency spokeswoman Debra Johnson, the state has one office with “bed-style cots” for COVID-19 isolation of foster youth, located on Delridge Way Southwest in West Seattle. But information about how many other offices have rollaways or cots is “not readily available,” she said. According to an advocate for foster children, at times foster kids end up sleeping on couches and floors.

DIGGING INTO THE ROOT CAUSE

Hunter’s department will likely have to answer more questions from legislators when lawmakers reconvene in January.

Rep. Tana Senn, a Democrat from Mercer Island who chairs the child-welfare committee in the House of Representatives and co-chairs the DCYF Oversight Board, faulted the Washington Legislature for the increasing numbers of youths staying in hotels. “I think we need to clearly point to us (the Legislature) as a place where we have fallen down,” she said, adding, “This comes out to money.”

“Foster care’s in a crisis,” she said.

The sky-high number of foster-child overnights in state offices in the latest period is drawing a mix of surprise, curiosity and resignation from the other state legislators with seats on the DCYF Oversight Board, which the Legislature created in 2017 to monitor the child-welfare agency.

“I’m a little bit shocked and curious why on earth we would have that many office stays,” said Republican Sen. John Braun of Centralia.

“There may very well be a reasonable reason [for it], but we shouldn’t accept that as what’s normal,” he added. “We should be digging into the root cause.”

Rep. Tom Dent, a Republican from Moses Lake, said he was displeased to hear the news. However, “I can’t pick on the caseworkers. They’re trying to take care of these kids. They’re doing the very best they can.”

The final annual numbers on hotel and office stays for foster children are expected to be released Tuesday by the state Office of the Family and Children’s Ombuds. Preliminary figures obtained by InvestigateWest show that, for the year ending Aug. 31, 60 percent of the 220 affected foster kids had multiple nights in hotels and other so-called “placement exceptions,” with nearly 70 of them spending six or more nights in such places. And the state subjected two dozen children to 20 or more nights in those settings.

Perhaps surprisingly, the role of the coronavirus epidemic in the uptick in combined hotel and office stays is limited, the data indicate. In February, before the pandemic had taken hold in Washington, the state made 183 “placement exceptions” compared with only 95 in February 2019. And the biggest year-over-year jump, between July 2019 and this July, from 101 to 227, happened after most of Washington’s counties had partially resumed public activities.

Hunter said the COVID-19 crisis has interfered with his agency’s attempts to control the hotel crisis. “We are focusing on this problem and would have focused on it more had we not had a global pandemic,” he said.

What’s more, “we’ve been slow about implementing some of the items in the budget because our financial staff got furloughed for 20 percent of July, so the COVID had an impact on slowing our ability to do this,” Hunter said.

Many of the potential solutions that he points to are ones that are now in place.

This year state lawmakers directed nearly $16 million toward preserving and adding beds for short-term foster care at facilities, as well as facility beds dedicated to long-term, intensively therapeutic stays for foster youth with serious behavioral problems. They also allocated $7 million to increase stipends paid to foster parents in hopes of providing additional foster homes.

That includes just over $5 million in funding for 21 special new long-term beds, more than $1 million in funding for 12 special new short-term beds, almost $2 million for about five special new “enhanced” long-term beds, and more than $7 million for an unspecified number of regular short-term beds.

“We expect to implement everything that’s in the budget” from this year’s legislative session, Hunter said, and that’s despite the state’s coronavirus-induced budget shortfall.

In fact, “we’re proceeding as fast as we can” to open up the 21 long-term slots for troubled youth in state care, he said.

Hunter said the loss of those special foster facilities, due to funding cuts during the Great Recession and rate freezes afterward, is one of two reasons that the number of placement exceptions has been climbing since 2017.

SOLUTIONS, COSTS AND OVERSIGHT

The other reason is perhaps more troubling.

“We’re seeing more young people with pretty severe behavioral health concerns,” Hunter said.

According to many observers, increasing the number of special treatment beds for foster youth in Washington State is key to solving the hotel crisis.

Hotel stays can cost taxpayers $2,100 or more per night — and that’s an estimate from 2017, when DCYF last updated that number, according to Johnson, the department spokeswoman. That mostly covers the cost of the state caseworker required to stay up all night watching the foster child in the motel and the cost of a security guard. Sometimes, another DCYF caseworker is needed. The hotel room generally costs about $150, the agency says.

By contrast, a foster family receives far less for caring for an adolescent foster child with the most severe physical, mental, behavioral or emotional conditions — just $1,612 for an entire month. For a child who ranges in age from 0 months to 5 years and doesn’t have any conditions, it is just $672 a month.

Braun criticized the cost of the office and hotel overnights. “It just seems like [a] very inefficient, expensive and, ultimately, unhelpful way for these children,” he said.

“We’ve let this get away from us,” he said.

The jump in kids kept in hotels and state offices is “probably one of the most expensive outcomes for the department,” said State Sen. Jeannie Darneille, a Tacoma Democrat who serves on the Oversight Board.

She said she wants the state agency to make use of the funding that the Legislature has allocated. However, “we need to do some data-crunching with the department,” she added, especially in light of the COVID-19 epidemic.

Braun, the board’s newest legislative member, is critical of the body’s work: “I don’t think we’re providing much in terms of actual oversight.”

When asked what the Oversight Board has done so far on the hotel-stay issue, both Senn and Darneille acknowledged shortcomings.

“Nothing specifically directly,” Senn said. “I can’t say that this has been one of the areas of focus in particular,” she added.

“Boy, that’s asking me to stretch my memory,” Darneille said in a separate interview. She said, however, that the Oversight Board was set up “to provide feedback to the agency,” not to create new programs.

MORE FOSTER FAMILIES

A persistent problem plaguing Washington’s child-welfare system has been a chronic shortage of people willing to take in the children who end up in the state’s care as a result of abuse, neglect or just plain poverty.

Dent, the Republican representative on DCYF’s Oversight Board and the highest-ranking minority member on Senn’s House Human Services & Early Learning Committee, thinks the problem behind the high number of foster children being housed in office buildings and motels is the state’s dearth of foster parents.

As of this summer, DCYF said it had 5,058 licensed foster homes and 88 foster-care group-home facilities in Washington State. Those serve the 7,600 foster children that the state had in its care as of August, according to the agency.

“We’re going to have to look at all aspects of the program, and number one, why don’t people want to be foster parents? I was a foster parent. I’m no longer a foster parent. You want to know why? Because they made it too hard to be a foster parent,” Dent said. He said he and his wife stopped being foster parents in frustration with the state’s bureaucracy about 10 years ago.

Annie Blackledge, the executive director at the foster-child and foster-family advocacy group Mockingbird Society, also underlined the importance of foster families in keeping children out of hotels and offices.

“It comes back to foster parent recruitment and retention, and having more homes than children,” said Blackledge, who is a member of the DCYF Oversight Board.

She pointed to Mockingbird’s foster-family model, in which an experienced foster parent with one or two free beds in his or her home serves as a respite home for six to 10 foster families, taking in foster children in support of foster parents who need a break or pinch-hitting in an emergency.

“We see a very high retention rate [of foster parents] for this approach,” Blackledge said. “Foster parents stay on longer, and young people [in foster care] have more stability,” she added.

Dorothy Edwards/Crosscut

Cathy Apgar plays outside her Marysville home with her grandchildren, children and foster children on Sept. 3. She has been a foster parent since September 2007 and participates in the Mockingbird Society’s foster-family program, taking in foster kids whose regular foster parents need a break.

But many foster-care observers maintain that solving the hotel-and-office stays crisis comes down to adding more long-term, therapeutic behavior rehabilitation services beds to the state’s supply. Those beds exist in specially trained foster families or in accredited facilities that are run privately, either for-profit or not-for-profit. The state itself does not operate these specialized facilities.

For its 2019 annual report, the ombuds office interviewed the regional administrators who oversee each of DCYF’s six geographic regions. The ombuds reported that those administrators “uniformly agreed the problem of placement exceptions is getting worse and is not necessarily due to a lack of licensed foster homes.”

“In fact, [they] noted many foster homes are empty while children languish in a series of hotel stays,” the ombuds office wrote. The ombuds report continued, “While these new populations of children have grown, the recruiting and training of foster homes remains tied to a traditional view of a foster child that does not address the placement needs for these types of youth.”

Scott Hanauer, who retired two years ago from Community Youth Services in Olympia after working there for 17 years and serving as its CEO, said there are many children in the foster-care system who don’t meet the formal state requirements for a behavior rehabilitation services bed but, in fact, need one.

Hanauer suggested that the issue comes down to a hesitance to fund the beds and a lack of public concern for the most-troubled foster children.

“They’re seen as kind of throwaway kids,” he said of the children who end up in behavior rehabilitation. “Their future is not seen as hopeful.”

“We know what works” for the treatment of those children, Hanauer said. “It’s just it’s not cheap, and you can’t cheapen it down.”

Hunter is confident that he can use the extra funding that the Legislature this year put toward both the long-term and short-term beds for foster youth. However, should the new funding come up short in addressing the hotel crisis, it will be next to impossible to find more money in the coronavirus-shrunken budget that lawmakers expect to be working with in the 2021 session.

This story contains information from previous InvestigateWest articles in InvestigateWest’s multi-year reporting project on Washington’s foster-care system.

InvestigateWest is a Seattle-based nonprofit newsroom producing journalism for the common good. Learn more and sign up to receive alerts about future stories at http://www.invw.org/newsletters/.