With the United States now facing its own serious coronavirus outbreak, it’s natural to wonder whether you’ll get the respiratory illness and what you can do about it. As of March 16, more than 3,900 cases and dozens of deaths have been reported in the US, according to the New York Times’s tracker. But due to a lack of widespread testing, it’s likely the outbreak is much bigger.

One respected modeler, Trevor Bedford, a computational biologist at Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center in Seattle, says there may already be around 20,000 cases in the US. Marty Makary, a professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins University, told Yahoo Finance that the number of current infections could be between 50,000 and 500,000. “We’re about to experience the worst public health epidemic since polio,” Makary said.

As further evidence of widespread unreported cases, Marc Lipsitch, director of the Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, pointed on Twitter to the CDC’s National Influenza Surveillance Report, which regularly tracks symptoms similar to those of Covid-19. He noted that symptoms such as fever, coughs, and sore throats are trending up, while confirmed flu cases are going down.

As the coronavirus spreads, it’s becoming a nationwide crisis that could severely strain our health care system, so we need to take collective measures now to protect ourselves and others. Here’s what you need to know:

1) How do I get Covid-19?

There are a lot of acronyms floating around, so first, just know that the SARS-CoV-2 virus (the coronavirus) causes the disease Covid-19. The virus is most commonly spread by close contact with infected people who are within 6 feet of each other. When they cough or sneeze, they send droplets into the air, where they can land in the mouths or noses of people who are nearby, or possibly get inhaled into the lungs. Droplets containing the virus can also land on surfaces and objects where the virus can survive for some time.

According to a preprint paper (a study that hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed) from researchers at the National Institutes of Health, Princeton, and UCLA who studied the novel coronavirus in a lab, it can survive for up to 24 hours on cardboard and for up to two or three days on plastic and stainless steel. (Another study suggests it can stay infectious for up to nine days.)

The danger of infection here is touching one of these surfaces and then touching your eyes, nose, or mouth. The CDC, however, says that “this is not thought to be the main way the virus spreads.”

Some diseases, like measles, can also be transmitted through aerosols, meaning that when someone coughs, tiny droplets filled with virus linger in the air, sometimes for hours, where others can breathe them in. Currently, there’s limited evidence of the coronavirus being transmitted this way, but it’s worth noting. One preprint found the virus in aerosol form in hospitals in Wuhan, and others agree that there is a higher risk of doctors and nurses being infected through aerosols. There’s also growing evidence of fecal-oral transmission, meaning you can ingest the virus shed in feces through inadequate hand-washing or contaminated food and water.

The good news is that transmission can be prevented. Good personal hygiene and social distancing can be very effective. “I’m not one of those people who normally goes crazy about hand-washing,” says Megan Murray, an infectious disease specialist and professor of global health at the Harvard School of Public Health. “Now I really am, because that will help reduce [the] virus on your hands.”

Washing your hands frequently and carefully for at least 20 seconds is better than using hand sanitizer because it actually destroys the chemical structure of the virus. Any old soap will break the virus’s outer coating, and you don’t need special antibacterial soap. If soap and water aren’t available, use hand sanitizer with 60 percent alcohol (no, this doesn’t include Tito’s vodka).

New research suggests that people may be most infectious early in the disease (and even before symptoms start), meaning that as soon as you start to feel ill, it’s important to self-isolate. You don’t need to be coughing to be contagious; the linked preprint suggests that somewhere between 48 and 66 percent of 91 people in a cluster in Singapore were infected by someone without symptoms.

This makes taking precautions now — like canceling your travel plans and social gatherings— even more important. The effectiveness of widespread travel bans, especially when community transmission is already occurring, is being hotly debated, but in general, minimizing social contact is the best method of prevention.

Avoid handshakes or hugs with people who’ve been out and about, and whenever possible, stay at least 6 feet away from others. This includes minimizing or avoiding play dates, sleepovers, shared meals, going out to eat, and visits friends’ and family members’ homes.

Also important to know is that according to one study from China, around 25 percent of all cases may originate in people who have no symptoms — another reason social-distancing measures are so important.

2) Oops, I think I touched my face. What are the symptoms of Covid-19?

The most common symptoms of Covid-19 are a fever, seen in almost 90 percent of patients, as well as a dry cough and shortness of breath. A study of 71 patients in China also suggests that a significant portion of coronavirus patients experience diarrhea, nausea, or vomiting, sometimes before respiratory symptoms begin. The World Health Organization (WHO) says these symptoms typically come on gradually.

Around 80 percent of Covid-19 cases are reportedly “mild,” but as James Hamblin of the Atlantic noted, that word can be misleading:

As the World Health Organization adviser Bruce Aylward clarified last week, a “mild” case of COVID-19 is not equivalent to a mild cold. Expect it to be much worse: fever and coughing, sometimes pneumonia—anything short of requiring oxygen. “Severe” cases require supplemental oxygen, sometimes via a breathing tube and a ventilator. “Critical” cases involve “respiratory failure or multi-organ failure.”

The incubation period before symptoms appear ranges from two to 14 days, but the median is 5.1 days. If you’ve been around someone who has a confirmed diagnosis of Covid-19 or displays its symptoms, the most responsible thing to do is to self-quarantine for two weeks.

3) But I’m young and healthy. Do I really need to worry about getting sick or spreading the virus to others?

Yes, you do.

The reason is that social distancing works best if everyone — young and old, healthy and infirm — practices it. No one has immunity, and everyone can get sick and spread the virus to others.

“The more young and healthy people are sick at the same time, the more old people will be sick, and the more pressure there will be on the health care system,” Emily Landon, an infectious disease specialist and hospital epidemiologist at the University of Chicago Medical Center, told Vox’s Eliza Barclay and Dylan Scott.

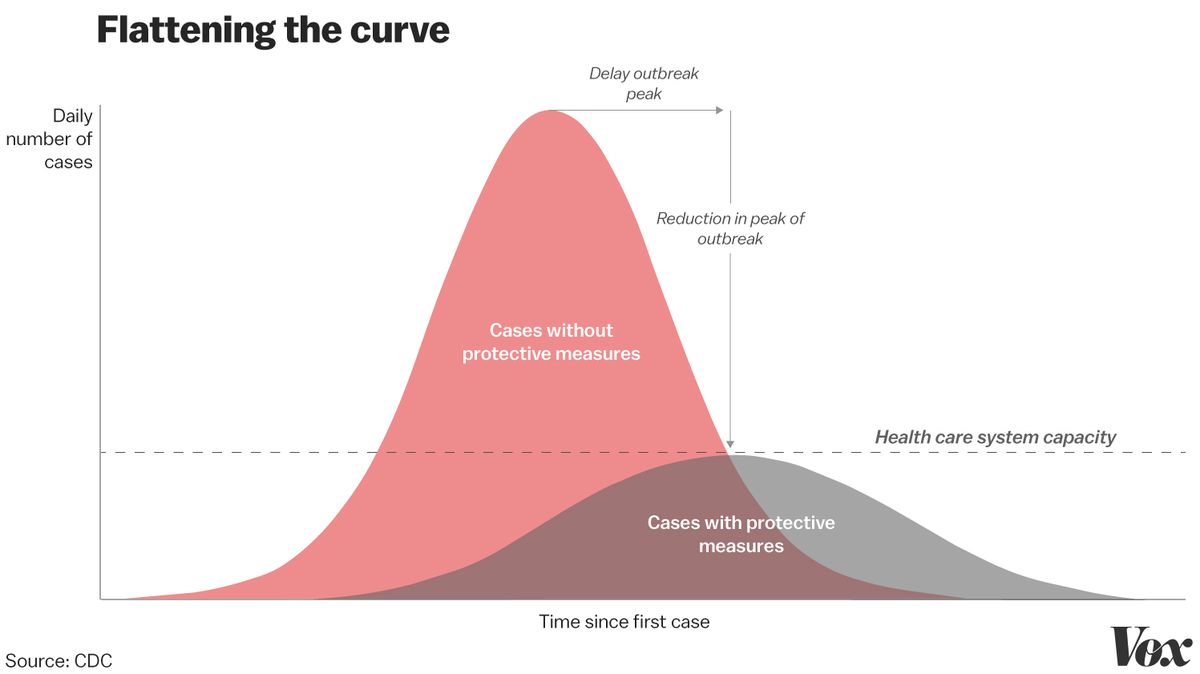

Without protective measures, one person on average infects 2.5 others, and cases will spread exponentially. That means hospitals and medical staff will quickly become overwhelmed. At least 5 percent of Covid-19 patients may need intensive care, and many require hospitalization for weeks.

Even if you’re not at a statistically higher risk of dying from Covid-19, it’s important to “flatten the curve” and adopt social-distancing measures immediately to prevent the most deaths.

Christina Animashaun/Vox

Christina Animashaun/VoxAlso, just being young and healthy is not a guarantee of mild illness. The epicenter of New Jersey’s outbreak of Covid-19, Holy Name Medical Center, had 11 confirmed Covid-19 cases on March 14, six of which were in the ICU, with ages ranging from 28 to 48.

4) I have a fever (or a dry cough). What should I do?

If you have one or more symptoms of the new coronavirus, call your doctor. If you are older or have underlying medical conditions, it’s even more important to call your doctor, even if you have only mild symptoms, according to the CDC. Before you go to your doctor’s office, Murray says you should call ahead so that medical staff can wear the appropriate protective gear and be ready to help take care of you without exposing others. Many health care facilities are requesting that you wear a mask if you have symptoms and are going in for testing.

Your doctor will determine whether you should be tested; if a test is ordered, you can expect a nasopharyngeal swab, where a tiny Q-tip is put up your nose a few inches — not a fun procedure, but it doesn’t hurt. It’s then sent to a lab and put through a process called a polymerase chain reaction, which detects specific genetic material within the virus. How long it takes to get results back varies, but in the US, it’s currently taking a few days.

If you’re concerned about the cost of getting tested — which Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA) estimated at $1,331 — the CDC recently committed to covering the cost of testing for all Americans regardless of insurance status, although when and how that will be implemented is yet to be announced. Currently, 1,000 insurers have waived treatment fees, and some cities and states like New York have said they will waive cost sharing for tests. This is important because “if [insurers] don’t cover treatment, you have to expect fewer people will go to get tested,” says Jennifer Flynn, who runs health care campaigns for the Center for Popular Democracy.

Many people who know they’ve been exposed are currently having difficulty actually getting tested. Flynn says her colleague developed similar symptoms after sharing a cab with CPAC participants, a conference in DC where multiple people fell sick from Covid-19.

That’s true even in Covid-19 hot spots. Helen Teixeria, a resident of Redmond, a suburb of Seattle, one of the nation’s outbreak epicenters, says she woke up last week with a tight chest, fever, and a dry cough.

First, she called the King County hotline and was told to call her primary care provider. Her doctor told her to go to the emergency room, where the hospital didn’t follow standard isolation protocol and medical staff did not wear basic protective gear. Teixeria said she was unable to get a Covid-19 test because they were being tightly rationed for high-risk and hospitalized patients. Nor was she allowed to get a two-view chest X-ray “so that I didn’t contaminate the X-ray room,” she says. A sympathetic nurse eventually slipped her off-the-record information on a private clinic where she might be able to get a Covid-19 test next week.

5) I’m definitely sick and still waiting to be tested. What else should I do?

After you call your doctor, stay home, says Tom Frieden, former director of the CDC. It sounds like overly simple advice, but it’s the best thing you can do. Next, you should self-isolate, including staying away from anyone you live with.

If you’re not in one of the CDC’s high-risk categories, trying to see your doctor may actually expose you further. “The single place you’re most likely to encounter people with coronavirus is the hospital, so that’s the last place you want to be if you’re afraid of getting infected,” Murray says. And if, in your quest to get tested, you go to multiple health care centers, you’ll be exposing health care workers in each location.

If you think you might have Covid-19 — and frankly, even if you don’t, so that you avoid possibly spreading it before you have symptoms — avoid all public areas. This means don’t go to school or work, and try to avoid taking public transportation, including ride-hailing services like Uber, Lyfts, and taxis. If you don’t have adequate supplies at home, consider asking friends or family to make a delivery to your door rather than going out yourself. Don’t let friends come visit while you’re recuperating; instead, stay connected by phone or online.

If you’re worried about quarantining in a home where you don’t feel safe, 24/7 help is available from the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Call 1-800-799-7233 or text LOVEIS to 22522.

6) What’s the best way to take care of myself at home?

“Self-care [for coronavirus] is very similar to other upper respiratory infections,” says Elisa Choi, an infectious disease and internal medicine specialist in the Boston area. Over-the-counter medications, like cough suppressants, can help minimize coughing episodes, and expectorants can help you cough stuff up.

Pain relievers and fever reducers like acetaminophen (brand name Tylenol) and ibuprofen (Advil) can help treat muscle aches and reduce fevers.

Although France’s health minister warned that anti-inflammatories like ibuprofen and cortisone could aggravate the illness, other scientists are skeptical.

“There are multiple assumptions that are made with that hypothesis that can’t be made without being tested,” Angela Rasmussen, a research scientist at Columbia University’s Center for Infection and Immunity, told Vox. “To my knowledge there’s no evidence that ibuprofen makes [Covid-19] worse.”

Choi also urges using common sense to manage symptoms. “If you’re feeling congestion, you can try taking a hot shower or steam,” she says. “Sleep and water are always good advice.” The CDC says that “drinking enough water every day is generally good for your overall health.”

Choi and other medical professionals warn against circulating misinformation about home remedies, such as what’s happening with an email erroneously claiming to be from Stanford. These remedies include holding your breath without coughing and keeping your mouth moist. Many of these “treatments” are unproven, and some can be dangerous. (For example, you can overdose on zinc.)

“This is really a time to stick with the facts,” Choi says. “Stay away from things that are being promoted for sale without a known background.” She recommends always checking with your doctor if you have questions about the veracity of a particular source. The CDC and WHO, as well as your local and state public health departments, are good sources of updated, verified information.

7) If I’m sick, how do I protect the people I live with?

Choi says that suspected or confirmed Covid-19 patients should stay in their own room and (ideally) not share a bathroom.

“They should try to stay as far away as possible from anyone else in the household, and at least 6 feet,” she added. If you do share a bathroom, avoid being in the room at the same time as anyone else. The WHO found that most of the transmission in China was between family members.

If the sick person feels up to it, ideally they should be the one to disinfect the bathroom after they use it. If your living situation doesn’t allow you to isolate yourself from others in your home, tell your doctor and/or health department.

The CDC has a complete guide to disinfecting commonly touched surfaces like “counters, tabletops, doorknobs, bathroom fixtures, toilets, phones, keyboards, tablets, and bedside tables,” and it recommends doing so every day. You can use one of the approved products or make your own, like adding four teaspoons of bleach to a quart of water. The CDC also recommends wearing gloves when touching possibly infected items, like used clothing or bedding, as well as when disinfecting commonly used surfaces. When you’ve finished, throw the gloves directly in the garbage — and then wash your hands.

Choi suggests washing your hands frequently to protect others in your household, and covering your nose and mouth when you cough or sneeze with a tissue that you throw directly into the garbage. If you’re feeling ill, don’t share cups, utensils, dish or bath towels, toothpaste, bedding — or anything else — with anyone. The coronavirus can stick around on surfaces for several days.

8) When should I seek additional medical care?

Choi recommends closely monitoring your symptoms. “It’s less about a number and more about the progression,” she says. Generally, a low-grade fever is considered less than 100.4, but older people are generally less likely to mount a fever response. The main thing to watch for is symptoms getting worse. For example, if you initially have a mild cough but start to have prolonged bouts, or if coughing becomes painful, she recommends calling your doctor again.

The CDC says that you should seek medical attention immediately if you have difficulty breathing or shortness of breath, persistent pain or chest pressure, an onset of confusion or the inability to stay awake, and bluish lips or face. If you do decide to go to the hospital, make sure to call ahead so the hospital can prepare to admit you without exposing others. If you already have a mask at home, this would be a good time to wear it; if you don’t, please don’t go buy one. There is a severe shortage, and medical staff need them.

Know that if you do go to the hospital, there is currently no treatment for Covid-19. Remdesivir, an antiviral drug, is in clinical trials, but right now, doctors are limited to providing supportive care such as supplemental oxygen.

9) How long do I have to stay isolated?

While there’s still a lot we don’t know, Murray says that you should self-isolate for at least 14 days after your initial symptoms. (There have been a few reports of patients shedding viruses for up to 28 days, but those appear to be outliers.) This means avoiding contact with everyone. (Read Vox’s guide to self-isolation here.)

For her part, Choi recommends minimizing all contact until your doctor or a public health department tells you that you are no longer contagious.

10) I already have cabin fever. My kids are bouncing off the walls. And I’m so anxious I can’t sleep. Help!

“Measures for pandemic control can be stressful,” Choi says, especially for people who may have challenges with being isolated. This feeling may get worse over the next few weeks, as current social-distancing measures are likely to be extended. Such measures can also cause financial hardship and stress for people who can’t work from home or won’t get paid if they don’t go to work.

Many people are experiencing cognitive dissonance about the ongoing normality of their daily lives, or, conversely, experiencing very rapid change. Be kind to yourself and others if you are struggling. Whether you’re afraid of getting sick or reacting to uncertainty, financial hardship, or a lack of information, anxiety is a natural response and you are not alone.

If you have preexisting mental health conditions, be aware that this may trigger new or worsening symptoms. (The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Service Administration has a 24/7 Disaster Distress Helpline, reachable at 1-800-985-5990. It also has an app with additional resources.)

No matter how stressed you feel, it’s crucial not to scapegoat others. This virus is not transmitted by or infecting any particular group. “I’ve experienced anti-Asian racism myself,” says Choi, and “it’s disrespectful, hateful, and not grounded in facts.”

Know that the situation is not hopeless; collectively changing behavior can go a long way toward controlling the spread of this disease. China has now closed all of its temporary hospitals as its case numbers continue to decline. But the social and economic repercussions of this pandemic may continue for months, so prepare yourself mentally for a long haul.

Do the small things that are in your control, like giving yourself a break from the news — put down Twitter — and maintaining normal routines as much as possible. If you’re at home with family or roommates, find ways to give each other space. Be creative about finding ways to exercise; YouTube videos are a great resource, if you can’t get outside. Talk to your loved ones about what you and they need to stay happy and healthy.

11) Can I get reinfected with Covid-19? And is it better to get sick to build herd immunity?

Japan and China have both reported multiple cases of people testing positive after initially recovering. It’s unclear if these were relapses or new infections. In four medical professionals in Wuhan, a test detected the virus’s genetic material up to 13 days after they stopped having symptoms, but finding genetic material doesn’t necessarily mean you can still infect others.

Once you’ve gotten sick, you might have some immunity, says Peter Hotez, dean for the National School of Tropical Medicine of the Baylor College of Medicine, but really the jury’s still out. “We don’t know, it depends on your antibody response,” he says. (A new, encouraging preprint showed that in some monkeys, reinfection of Covid-19 does not occur.)

Hotez suggests that recovered patients do seem to produce antibodies. He pointed to a new paper on the possibility of using blood from recovered patients as a treatment, or even a preventive measure for first responders.

Still, recovered patients may also experience lasting effects; doctors in Hong Kong said that some recovered patients had a 20 to 30 percent drop in lung capacity. Another alarming preprint suggests some patients may have permanent kidney damage.

What about building herd immunity?

The UK government on Friday announced a strategy of allowing the virus to spread to build herd immunity, although it since walked it back and is recommending self-isolation. For herd immunity to control Covid-19, more than 60 percent of the population will need to get the disease. The logic is that extreme lockdowns now won’t stop the virus from returning in the future, when those measures are loosened.

The problem is that many people may succumb to the disease in the meantime, and that by not attempting to control the spread, hospitals and medical systems will be overwhelmed. Achieving herd immunity in the UK would require more than 47 million Britons to be infected, which could mean around hundreds of thousands would die. Immunity might also not last long enough to help, as with the flu, where new strains emerge each year. Relying on herd immunity also conflicts with WHO policy. Anthony Costello, a pediatrician and former WHO director, tweeted, “Is it ethical to adopt a policy that threatens immediate casualties on the basis of an uncertain future benefit?”

There are two likely ways this pandemic will end now that the virus is so widespread: 1) So many people will get it that we’ll develop a natural herd immunity, a term that is used to describe people getting a disease and becoming immune as a result, or 2) we’ll make and widely produce an affordable vaccine. It is very unlikely that we’ll see a big decline in Covid-19 cases solely due to the weather getting warmer. Plenty of places where there is currently warm weather, like Singapore and Australia, have Covid-19 cases.

There are no easy answers. “We have to recognize that we’re gonna start seeing a fair number of hospital admissions, especially ICU admissions,” Hotez says, “and we have to ask the hard questions about what treatment we can do now.” Developing a vaccine will take many months at best, which is why in the meantime, changing your behavior is so important.

Ultimately, “this is a new disease, so while we’re trying to make new predictions about risk, all bets are off,” says Choi. “We’re learning as everything is evolving actively in real time.”

Lois Parshley is a freelance investigative journalist and the 2019-2020 Snedden chair of journalism at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. Find her on Twitter @loisparshley.