Advertisement

The Checkup

Despite the crises of 2020, parents can realistically expect that children born today will outlive them. That wasn’t always the case.

Rule one of Hollywood screenwriting is, “don’t kill the kid.” Well, actually, rule one is more famously, whatever you do, don’t kill the dog. But if you happen to be a pediatrician who occasionally moonlights as a screenwriter, children come up more frequently; my limited life writing television scripts has involved being hired because someone wants high-stakes pediatric drama, and then being asked to delete story lines about seriously ill children, because sick and dying children are hard to watch. It’s not easy to construct high-stakes pediatric drama without endangering children, though I’ve tried.

Over the past few years, as I have been researching and writing a book that traces the remarkable story of the battle against infant and child mortality, I was digging deep into fascinating stories from past centuries involving the parents of sick and dying children. I read the sorrowful words of everyone from Mark Twain and Charles Dickens to W.E.B. Du Bois and Charles Darwin, and yes, I wanted to tell those stories and remember those lost children, who in my mind had come to hover over almost every historical room, to stand quietly in the shadows of every family portrait.

But I wanted to write about these past sorrows as part of a trajectory that leads to a happy story about children not dying. I wanted to understand and to celebrate what I think may be our most noble project as humans, and noble precisely because it never was a single project: We have dared to imagine a world in which parents can expect their children to live to grow up, and we have taken many steps (giant steps and, if you will, baby steps) in that direction.

This was the world of my training in pediatrics in the 1980s: Every child should live to grow up in health and safety. There are no acceptable accidents; the world should be made safer, with car seats, bicycle helmets and campaigns to make sure babies are put down to sleep in the safest position. Premature infants can be supported in the newborn intensive care unit; congenital heart problems go to the operating room; terrible infections need antibiotics — until you have vaccines to prevent them. This was what drew people into pediatrics: Our patients would outgrow us.

When I described the idea for this book to publishers, I found myself starting with the phrase, “We are the luckiest parents in history.” And that’s how I have come to be publishing a book during a terrible year with the seemingly incongruous title, “A Good Time to Be Born.”

Because, believe it or not, even in 2020, parents in the United States and in many other countries, and not just the very richest, are among the luckiest parents in history. We can, for the most part, hope and even expect to see our children live to grow up, and we live in a society shaped and colored by that expectation. And for all of the anxieties and terrors of this present moment, as parents, we are actually on the lucky side of a divide that separates us from the parents who came before.

At the beginning of the 20th century in the United States — my grandparents’ moment — as many as 20 percent of the children born didn’t make it to their fifth birthdays, and earlier in human history that was probably far higher.

The parents who came before, all through history, loved their children, cared for their children, but expected children to die. When Dickens’s infant daughter, Dora (named after the child bride in “David Copperfield”) died suddenly in 1851, after developing seizures, Dickens wrote to his wife, Catherine, who was away at the spa town of Malvern, taking a cure, “We can never expect to be exempt, as to our many children, from the afflictions of other parents.”

That same year, Charles Darwin took his 10-year-old daughter, Annie, to that same spa town in search of a cure for her illness, which different biographers have identified as scarlet fever, influenza or tuberculosis. He tended her carefully and sent his wife, Emma, regular updates: “We have again this morning sponged her, with vinegar, again with excellent effect.”

But the vinegar was not enough, and two days later, he wrote: “She went to her final sleep most tranquilly, most sweetly at 12 oclock today. Our poor dear dear child has had a very short life but I trust happy, & God only knows what miseries might have been in store for her.”

My grandmothers knew that a lot of children didn’t live to grow up, that if you asked any group of adults born, like them, at the end of the 19th century, having their own children in the first decades of the 20th, most of them had lost a sibling, lost a baby, lost a school friend. They both grew up among the urban poor, and their own childbearing experience, in the poorer parts of immigrant Brooklyn, in the East End of London and then the Lower East Side of Manhattan, took place at a time when social reformers were taking on the project of bringing down infant mortality, especially among the urban poor.

In 1906, a British physician, George Newman, published “Infant Mortality: A Social Problem,” citing mortality rates all over Europe of 100 to 300 babies out of every 1,000 dying before their first birthdays, “a vast army of small human beings that lived but a handful of days.” This was the historical moment when people in many countries began counting those deaths, as we still count them, and using them as an index to a society’s well-being.

Collectively, as human beings, we changed the game. It took science, medicine and public health, it took sanitation and engineering and safety legislation, and it took many different kinds of education and parent advocacy. And it took vaccines and antibiotics, those 20th century game-changers.

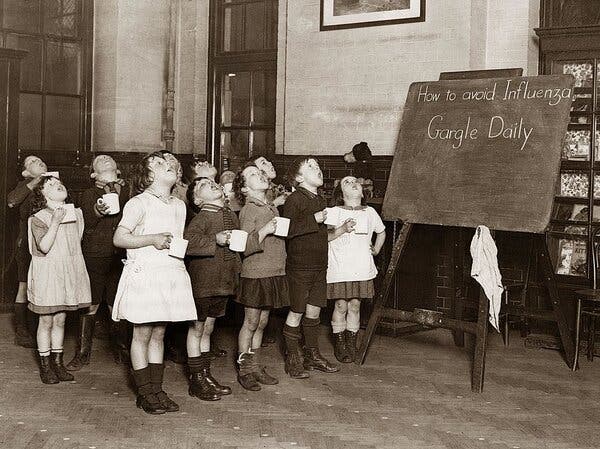

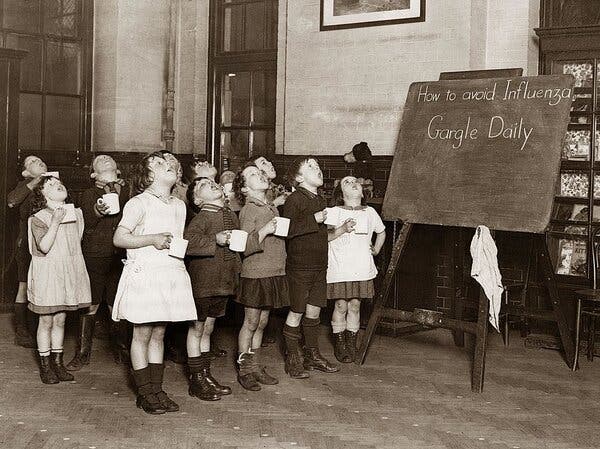

Keeping children safe, and making the world safer for them, was the sum of many different efforts, from international campaigns to laboratory experiments to local endeavors. Before there were antibiotics, before there were any vaccinations except for smallpox, there were the nurses who went door to door in the tenements of the Lower East Side in the summer of 1908, talking to mothers about how to prevent the cholera infantum, or summer diarrhea, which was expected to kill 1,500 babies a week.

And there were mothers who listened: In the district where the nurses were deployed, there were 1,200 fewer infant deaths than the previous summer; everywhere else, the death rate was unchanged. Dr. S. Josephine Baker, who directed the project, wrote “I had learned one certain thing: heat did not necessarily kill babies.”

We should not expect children to die; we should expect them to live to grow up; that was the foundation of my training in pediatrics, and the joy of working in this field. It was not a single project, or a simple project, and it is by no means a complete project; infant and child mortality rates remain unacceptably high in many parts of the world, though they have come down everywhere, and alarming disparities persist in this country, where the infant mortality rate, as well as the maternal mortality rate, remains notably higher among Blacks and other minority groups.

But even if we make the world more equitably safe, even if we improve on different aspects of child safety and child health, we know in our hearts as parents (and as pediatricians) that it will never be perfect. There will always be dangers, and there will always be tragedies. We have to rededicate ourselves to the struggle against the plagues — medical and social — that continue to strike down children, including infections, malignancies, accidents and violence.

But we have come, already, to a place that would look to the parents of a century ago like a place of privilege and safety, and, yes, good luck. And perhaps if we credit the science and medicine and public health and advocacy and education that brought us — and our children — to this place, we can believe in our collective ability to take on the complexities of this new pandemic and to take ourselves and our children to a new safety.