Advertisement

“Such a Fun Age” explores the toll of emotional labor on a black babysitter. “I like the idea of all of these people freaking out,” she says.

For six years in her 20s, Kiley Reid spent most of her days with toddlers — wiping chins, cutting crusts off bread, remembering their favorite songs.

“The reward of being with the same family and watching a child grow for four or five years was really wonderful,” Reid, now 32, said of her time as a babysitter. But the experience also got her thinking about how race and class interact in transactional relationships, and what it means to sell emotional labor.

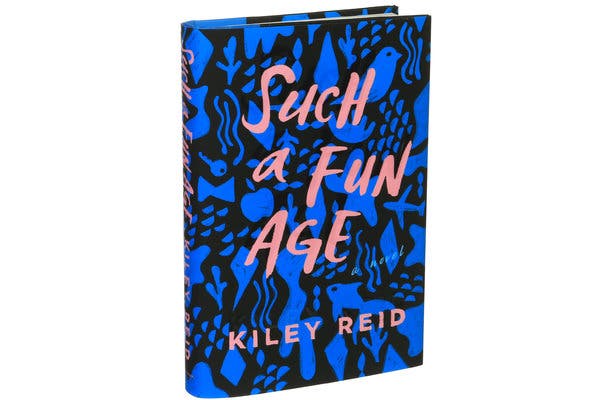

Reid explores these questions in her debut novel, “Such a Fun Age,” out Tuesday. Reid’s book, for which Lena Waithe has already bought the screen rights, revolves around the intersecting lives of Alix, a privileged white mom in Philadelphia; Emira, her 25-year-old black babysitter; and Kelley, a white man Emira ends up dating. An incident in the beginning of the book, when a stranger accuses Emira of kidnapping Alix’s toddler, sets off a series of events that force the characters to reckon with their biases.

The novel is inspired by Reid’s babysitting years, but it’s not autobiographical. “I was more inspired by the feeling of being in somebody else’s home as your job,” she said, “and the relationship you form with someone for $16 an hour.”

As Reid prepares to release her novel, she discussed mid-20s angst, the effect of race and class on relationships, and more.

Tell me where you got the idea for this book, and why you decided to write it.

I definitely started from wanting to explore the awkwardness of transactional relationships — but also bigger themes of ownership, from the small petty ones like “Oh, well, she’s our sitter” or “I knew him, so he’s mine,” to the awkward history of black women raising white children in this country. That just comes flooding back, no matter whether you like it or not, in certain interactions.

What was your experience babysitting in New York City?

I think the fact that I was coming from a relatively similar class background as a lot of the moms that I babysat for set me up to be friendly with them in ways that other nannies couldn’t. Those nannies are in very different situations, and the stakes are so much higher for them. If the event in the beginning of the book had happened to me in a grocery store, it would have been different. One, I’m a light-skinned person and colorism is a real thing. And two, my support system means I wouldn’t say “Oh, this is my fault, I did this,” the way Emira does.

In the aftermath of the incident at the grocery store, Alix and Kelley both claim to be trying to protect Emira. But their preoccupation with her life doesn’t seem to involve her lived reality. What do you make of that distance?

Emira’s dealing with a very “humans in late capitalism” period of her 20s, which leaves her questioning everything. Am I holding my friends back? Should I be living in a different apartment? How do I make more money? What do I want to do? With this novel I really wanted to show a bunch of individuals who are well intentioned and obsessed with their own behavior. And they are so concerned with how they can be good for Emira that they’re blind to questions like: Why doesn’t she have health insurance? Why do these things happen? I like the idea of all of these people freaking out about their individual reactions so much that they completely overlook the big problem.

Alix tries to befriend Emira, but she’s also Emira’s employer. What about that transactional relationship did you want to explore?

The biggest thing I wanted to show in Alix was her full complexity as a human and her ability to, one, want a really great babysitter for her kids, two, have a bit of a crush on this girl, and three, kind of do her own self-care and be able to feel good about the fact that she cares about this black woman. I think that all of those things can happen at once. I remember when I was a child, I had white friends whose parents loved me and would want me over all the time. But if their daughters ever thought about dating a black man, they would not allow it. And I think that that love for me and that racial bias can exist very harmoniously. And I think that scares people a little bit, to think, “I can be a lovely person and still be racist as well.”

Something I wanted to play with in this novel, too, once I knew the characters, was Alix’s isolation and her loneliness and what that brings out in her. Capitalism often sets us up to work by ourselves, to seek out friendships from the nearest person. Alix’s loneliness drives her to think and do some weird things.

I think for Emira, transactional relationships look like emotion, when it’s work. Emira is giving her all to this child, and the fact that it’s no longer beneficial to her and she needs to be able to go to the doctor and whatnot gets really complicated.

Emira is very reserved at work, and Alix tries to get to know her by creeping on her phone. She has trouble reconciling what it means that Emira listens to Young Thug but also knows the word “connoisseur.” What do you make of Alix’s obsession with Emira?

Emira’s so other to Alix, and does and wears and says so many things that she and her friends would never say, she’s constantly searching for a connection. And I think she’s searching a little bit to put Emira into a box of what kind of language can I use with you, what kind of things can I show you that you’ll be excited about — “O.K., well, if you like Young Thug, maybe I don’t know you.” “Oh, look, you used the word ‘connoisseur,’ maybe I do know you.” I think she’s so afraid of misstepping with Emira, and seeming racist, that she continually tries to find things out about her, not because she thinks she’s interesting but because she wants a way in. And I think a lot of people do that. I’ve had those cringey moments where I just meet white people and they want to call me “girl” and “boo” immediately to make a connection with me.

But Alix is almost too charmed by how different Emira is — there is a bit of fetishizing. So many things that young low-income black women do end up in Vogue three years later, and there is this fascination with their style or how they talk or things they say, and Alix can’t get enough. But the fact that she’s paying her doesn’t really mean anything to Alix; she doesn’t understand that there’s a boundary that she shouldn’t be crossing.

It’s tempting to see Alix and Kelley in opposition to each other, but neither really ends up being the hero or the villain. How do they interact with race differently?

Alix sees racism as the biggest no-no, not because she thinks it’s the most wrong, but because it’s the most wrong to appear to be, I think. She looks to Emira to confirm everything she wants to hear. I think that need is really, really dangerous. If that need is guiding all of your actions, then things like having mold in poor schools or black women dying earlier than other demographics, those things kind of go away and you’re just like, How can I fill my little goodness meter? That’s really dangerous.

Kelley has a lot of black friends. He’s not one of those people who doesn’t see color, and I don’t think he believes in that, but he doesn’t think about himself contributing or benefiting from white supremacy in a way that would make him self-reflective about it.

The relationship between Kelley and Emira highlights the potential awkwardness of interracial relationships. There were a few times when Kelley did stuff that was not O.K., and Emira kept thinking, “All right, I’m going to let this one slide.” What about interracial relationships did you want to explore?

I really wanted to watch Emira figure out what kind of person Kelley was. In her mind I don’t think it’s “Is this person good or bad?” but “Can he get it?” I think that’s something a lot of people in relationships go through. Blackness means such different things to so many people, and to flatten that experience I think is almost anti-black. Kelley has to be good for Emira and her blackness, that is it. And she’s just trying to figure out those things. I think she’s also like, Is this guy good in bed? Is he funny? Can I bring him around my friends? Those things are just as important.

The dialogue between Emira and her friends, who are diverse in class, culture and complexion, feels very millennial and of the moment. What did you want to highlight through their interactions? What did you hope to depict about mid-20s life and why?

My biggest priority when depicting Emira’s group of friends was to make it completely apparent why these girls gravitated toward one another. In addition to having them absolutely enjoy each other, I wanted to put them on different class trajectories and see how they would respond. I’m fascinated by how money changes friendships, and how class solidarity can weaken friendships or hold them together.

What are you most excited to see onscreen in the Lena Waithe adaptation?

There are several different types of black women in the novel, with varying skin shades, lifestyles and hair textures, and the potential for what that can look like onscreen is very exciting.