Brooke Benoit starts her day with yoga – a tranquil practice she enjoys while her seven children are still asleep. This is her time, before the Benoit-Elkaoui clan come alive.

The younger children start to wake and help prepare breakfast before setting their own homeschooling pace for the day, often involving arts and craft and free play.

From their home in Aourir, a small town in Agadir along Morocco’s southwest coastline, the teenagers usually get up after midday and pursue whatever activity they had planned the night before. It might be painting landscapes of the palm- and argan-covered hills around their home, reading books, playing video games or working on an upcycling project.

Benoit, 47, grew up in Portland, Oregon, where she first began homeschooling her children 18 years ago. When her eldest son, Badier, was just three, a neighbour popped into her home suggesting she enrol her toddler into the local nursery.

“I hadn’t thought about my schooling options at that point,” says Benoit, the author of How to Survive Homeschooling – described as a “self-care guide” for homeschooling mothers.

‘I was going to do all this hard and loving work of mothering him and then hand my child over to someone else … I knew I could do it and do it better’

– Brooke Benoit, homeschooling parent

She is also the founder and editor of the Fitra Journal: The Muslim Homeschool Quarterly Journal, a quarterly that provides advice on how to raise well-rounded children

“What I did know was I was going to do all this hard and loving work of mothering him and then hand my child over to someone else to continue teaching him for most of his waking hours. I knew I could do it and do it better.”

In 2010, she and her then husband relocated to his native Morocco, but the couple were disappointed by the state of the local schools. “The ones we saw had no play area, they smelt like disinfectant and they were proudly pushing academics on three-year-olds,” she says, “while we had crates of bright, engaging materials already at home.”

Benoit chose a Sudbury-style or “democratic” approach to home education, where children educate themselves.

“I basically foster opportunities for them to learn what they need to. They have taken various classes, used tutors, and taken online courses, used apps and books to learn from – by any means necessary,” says Benoit.

Her biggest pull to homeschool was a belief in “an innate desire to learn”.

“I didn’t want to see that crushed in my children by an overstressed school system, [so] we just kept our eldest out of school a little while longer … until he started university.”

Learning in the Middle East

Millions of children study in primary, secondary and tertiary education across the Middle East and North Africa.

But with Covid–19 declared a pandemic earlier this year, schools shut their doors and sent children home. In a matter of weeks, an estimated 100 million children in the Middle East stopped going to school.

Arab governments were quick to adapt and introduce alternative ways to educate children in their homes. Egypt’s Ministry of Education added online lessons and electronic books to its website; Iraq created a YouTube channel with a series of lectures for different age groups; and Jordan produced several online platforms for children, teachers and also for student-parent-teacher communication.

An impressive feat for a region where homeschooling for local citizens isn’t usually encouraged, or supported. Statistics are not available on the number of homeschoolers in the region, but most governments prefer and encourage their local population to attend formal schooling.

In Qatar, the Ministry of Education issued a decree in 2001, stating attendance at primary and secondary schools was free and compulsory for Qatari nationals, but remained optional for expatriates. It’s a similar case across much of the Middle East.

And in Turkey, all Turkish children from the age of six must attend school, but expats are free to choose their own path. Arwa Eltaweel, 30, a mother of one, is doing just that.

In the garden of her apartment in Istanbul’s Uskudar neighbourhood, Eltaweel can be found guiding her son Yahya, eight, through his afternoon activities.

After reading a book together, Yahya plays with a jar of worms, giving them names and characters, and then takes a closer look at them under his microscope.

Playing with simple things, usually found in nature, is in keeping with the Waldorf method of education that Eltaweel favours in her homeschooling approach.

The founder of Waldorf education, Rudolf Steiner, an Austrian philosopher and social reformer, believed that by playing with simple things – like twigs, pinecones, sand – a child’s imagination is given the creative freedom to conjure up endless stories and games. And a daily connection to nature is a big part of the method, also known as the Steiner approach.

“We now know how important nature is to nourish the soul of not just children but adults too,” says Eltaweel, who moved to Turkey from her native Egypt in 2013 with her husband Ali Nagy. She started teaching her son at home four years ago. “Being in nature helps a child with their psychical and psychological needs. We live in an age where gadgets and technology blind us to the beauty of the world around us. But there is so much to learn from it.

“Most of our time is actually spent outside the home. We visit forests, go camping, learn about astronomy by actually seeing constellations in a clear night sky. Nature teaches our children so many things that can be taught better by living it, rather than through pen and paper,” says Eltaweel, a PhD candidate in sociology at Istanbul Sehir University.

She says that in Egypt, homeschooling has become a more viable option in recent years, as she believes it’s because education standards have fallen but the cost of it has risen.

Both Egypt and the UAE have systems in place to support home learners registered at a school within the country. These pupils follow the national curriculum from home, with the child able to take regular exams at school.

‘[Homeschooling] requires a legal framework, which is not available in most countries of the region’

– Maysoun Chehab, Unesco

But Eltaweel is quick to point out that this isn’t the same as homeschooling, which “allows a child to follow a more holistic education not limited by a curriculum that is set in advance, and there are no exams to sit if they don’t choose to”.

The lack of accreditation some types of home learning offers can leave some parents feeling wary. But this need not be an impediment to homeschooling, according to Maysoun Chehab, education programme specialist at Unesco’s Regional Bureau for Education in the Arab States. “Today there are several structured programmes that allow homeschoolers to sit exams, get qualifications and go to university if they so wish,” she told Middle East Eye.

But Chehab says there are still many issues facing homeschooling. “It requires a legal framework, which is not available in most countries of the region,” she says.

And the real challenges, according to Chehab, lie in “adult illiteracy rates, available curricula and parents’ preparedness”.

A home-based style of education may also lack popularity in the Arab world because of a lack of Arabic language support. “Everything I read on homeschooling was in English,” Eltaweel says. “When I was researching there wasn’t much available in Arabic.

“But now there are resources like Alta’leem Almarin,” she says, referring to an Arabic language website that offers information on alternative forms of education.

Eltaweel has also started her own blog that she hopes will help homeschooling gain popularity in the Arab world, which she says is suffering from a “lack of vision”.

“There is no imagination. People can’t visualise what they are capable of achieving for their children and think homeschooling is impossible,” she says.

“I’ve heard a lot of parents say they don’t trust themselves with their own kids’ education, that they are not capable of doing it. I’ve heard this a hundred times. You can do it, once you have the intention, parents know their children better than anyone else and really are the best teachers for them.”

‘It can be lonely’

In educating your children at home you are also allowing them to “know themselves” and know who they want to be, says Brooke Benoit – who is raising a troop of wannabe scientists, engineers and artists.

The single mother says she enjoys seeing her children, aged between five and 21, “freely and wholly be their pure selves”, and that’s by creating an environment at home without “external influences pressuring them into artificial norms”.

All of them participate in a youth centre she co-founded, called Amsmoon (which means “the gathering place” in Shilha, the local Amazigh language spoken in the area), and two are active in engaging with the local community and helping to run it – going against the stigma of homeschooled children being socially awkward.

Benoit’s eldest son, Badier, 21, like all his siblings, has never attended a mainstream school, but is studying online as a distance-learning university student, hoping to join the campus later this year.

Although he enjoys the “freedom” of learning at home, there are some drawbacks.

“It can be lonely, which I don’t like, and sometimes it can be hard to fit in because we don’t have the same experiences as other people,” he says. “But it has given us the opportunity to learn better and to build our own discipline – it makes us self-sufficient.”

Benoit was inspired by the work of American education reformers John Holt and John Taylor Gatto.

In his popular book Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling, Gatto wrote: “Children learn what they live. Put kids in a class and they will live out their lives in an invisible cage, isolated from their chance at community; interrupt kids with bells and horns all the time and they will learn that nothing is important or worth finishing.”

Schools were designed to produce a next generation of conformity, of compliant, literate workers, trained to take orders and generate more money for the companies they worked for, wrote the late Gatto.

“School was looked upon from the first decade of the 20th century as a branch of industry and a tool of governance.”

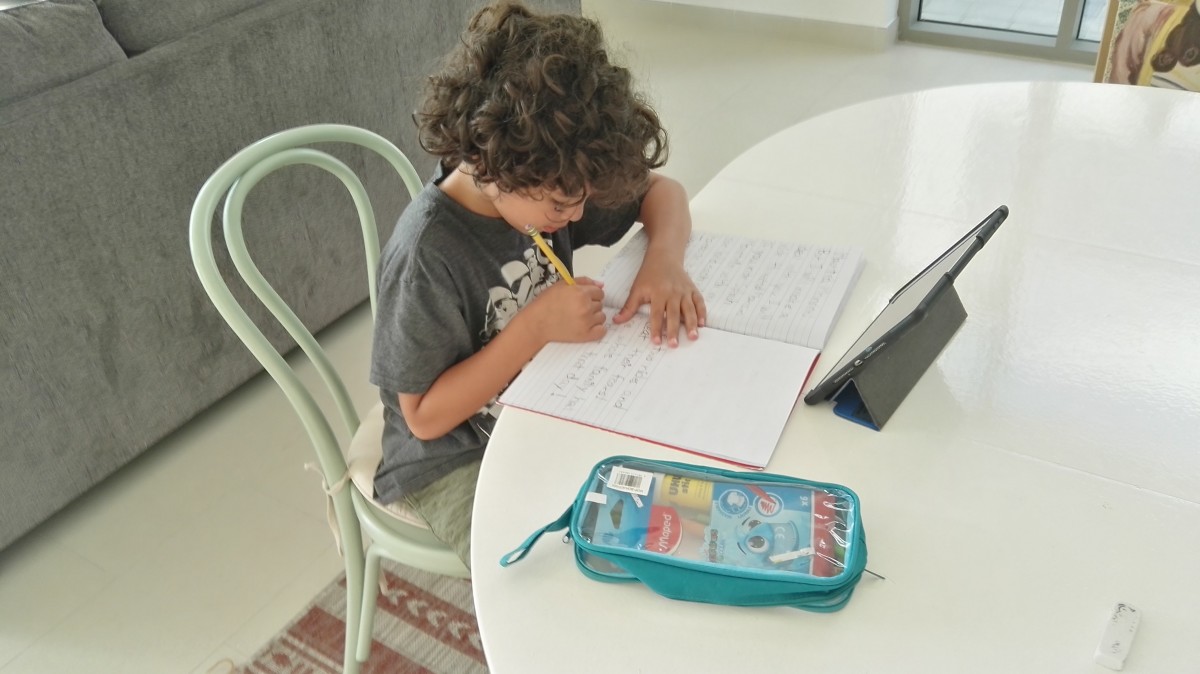

Some parents prefer to follow a set curriculum and recreate a school experience at home. In Qatar, Eritrean-Canadian mother of four Hanim Johar has been homeschooling her sons, aged 14 and 12, and her 10-year-old daughter since 2016. Her eldest attends a mainstream school in Doha, as he prepares to apply for university.

Unlike Benoit and Eltaweel, she prefers a more structured method of learning, following the Calvert Academy curriculum from the US.

The programme is one of many now available in the competitive homeschooling market. For a fee, parents are provided with lesson plans to structure their teaching day, along with interactive online courses for older children that can be customised to their needs.

It’s a Monday, which means it’s maths for the Johar family and breakfast is followed by two hours of study. After lunch and prayer breaks, the family studies collectively until 3pm, with Hanim studying herself for a Master’s in general psychology. Afternoons are kept free to watch educational programmes or to play favourite sports.

Johar noticed changes to her children’s behaviour when they started school, whereby they seemed withdrawn and tired and less communicative at home. This, combined with a lack of facilities at their school – no sports equipment and a small outdoor play area – led the family to choose home education.

“Homeschooling works for us, we haven’t looked back – the kids are better-behaved since leaving the school system and less stressed,” says Johar. “They are more independent with their studies, they love reading and are always picking up books to read.

“We feel closer as a family. I’ve also noticed the siblings have stronger bonds, they are more caring and doing favours for each other.”

Learning in the time of corona

But being forced to become your child’s teacher at home doesn’t appeal to everyone. In Dubai, Marwah Elimam, an Egyptian-American, had to take on her eldest son’s schooling after the coronavirus lockdown was introduced in March, but is desperate for life to get back to normal and for schools to reopen.

“Our biggest challenge has been the amount of work that needs to be done and the overwhelming amount of live meetings that teachers required. Also, having a six-year-old sitting in front of an iPad for a full school day is not fair and not always feasible,” says Elimam.

“First graders need guidance, explanation and help manoeuvring on their app. Some mothers’ lives have stopped and they’ve been glued to their kids to make sure things are done right.”

Elimam, a fashion designer and artist, is raising her two sons aged three and six with her husband, Ahmad. She is one of millions of parents juggling work, household chores and teaching – and the pressure is building up.

“I’ve had mothers of younger children tell me they spent the day crying and others feeling drained mentally from keeping up with the workload and supporting their kids while worrying about financial pressures,” she says.

And it’s a similar case for Norah Quronfleh and her family in Amman, Jordan.

“In Jordan, online learning was imposed on to the schools by the government because of the pandemic, so parents didn’t really have a choice in the matter,” she says.

Her children, aged eight, five and one, are happier following a shorter day studying at home than they would at school, but frustrations at being indoors are mounting.

“Interaction with their peers is really important in my opinion,” says Quronfleh, a primary school teacher. “Coronavirus has made this feeling of seclusion more intense because you can’t see friends or family. Children become set in their ways and will not be as tolerant to accepting or dealing with different personalities when they go back to school.”

Countries such as Iran have already reopened schools, while others are still watching and waiting. As the world slowly recovers from the effects of the pandemic, with shops, restaurants and places of worship reopening, speculation of a second virus wave may mean educating at home remains a choice for some and a necessity for many.

Saudi Arabia’s minister of education, Dr Hamad Mohammed al-Sheik, has said the country’s online distance learning programmes will continue even after the pandemic has passed “to address the problem of school dropouts”.

Thanks to the pandemic, more parents have started to consider homeschooling as a viable long-term option, including some parents that Brooke Benoit has been working with in Morocco, especially now that there are systems in place.

But rather than a “forced education of children at home” because of Covid-19, Arwa Eltaweel says she hopes that people will experience real homeschooling.

“I mean mixing with other homeschooling families, going to sports events, on outings to museums and galleries and learning with your children,” she says. “Because it is truly enjoyable and beneficial, not only for children but for the parents too.”