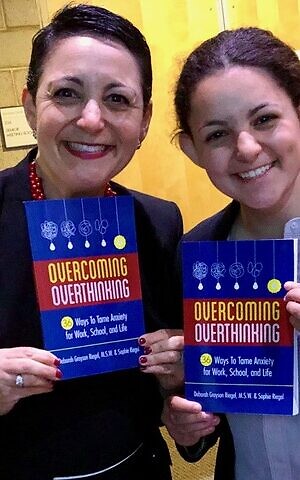

A Jewish mother and daughter from New York have teamed up to write two books about coping with anxiety disorders, the most common mental illness in the United States. Deborah Grayson Riegel, a professional speaker and executive coach, and Sophie Riegel, a 19-year-old freshman at Duke University, write from personal experience. Deborah suffers from three anxiety disorders, and Sophie from four.

Upon first meeting this high-achieving duo, it isn’t apparent that they have faced — and continue to face — considerable mental health challenges. They have found ways to flourish despite their struggles through turning to psychologists and psychiatrists for help, and supporting one another in rough patches. Recently they decided to take the best from what they learned from mental health professionals — and from one another — to share their hard-earned wisdom with parents, teens, educators, and others seeking strategies for alleviating anxiety.

Written jointly, “Overcoming Overthinking,” is presented as a conversation between mom and daughter. Accessible and with a welcome touch of humor, the book offers 36 strategies with catchy names, including “Learn Your Launch Sequence,” “Challenge Your Catastrophic Thinking,” “Recognize a Mazel Tov Moment,” “Name It To Tame It,” and “Find A Sit-In-The-Shit Friend and A Pull-Me-Out-Of-The-Poop Friend.”

‘Don’t Tell Me To Relax!’ by Sophie Riegel (Indie Books International)

Separately, Sophie wrote “Don’t Tell Me To Relax,” a compelling and candid memoir of her years as pre-teen and teen with anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder, trichotillomania and panic disorder. While Sophie reported that the book has been well received by a broad audience, she first and foremost wanted other teens with anxiety to see themselves in her story.

“I was hoping that I would be getting feedback from teens saying, ‘You really opened my eyes, you really understand me,’” she told The Times of Israel.

Mental health professionals are already praising her work. “Reading Sophie’s perspective and real-life, first-hand experience is great for teens to know they’re not alone and that they can fight through and overcome this immense obstacle. Sophie’s attitude and accomplishments in spite of her struggles are nothing short of inspiring,” said Bette Levy Alkazian, a licensed marriage and family therapist in Westlake Village, California.

Deborah Grayson Riegel and Sophie Riegel show off ‘Overcoming Overthinking,” the book the co-authored on strategies for handling anxiety. (courtesy)

Fran Mendelowitz, a licensed clinical social worker in Bellmore, New York, praised the Riegels’ “strategic, action-oriented approach to coping with mental health issues [that] provides their readers with hope and allows them to take an active role in their treatment process.”

Mendelowitz said she’s in favor of lay people like the Riegels publishing self-help books on mental health as long as they provide resources and encourage readers to seek professional treatment.

According to family therapist Alkazian, the content of these books is “very relatable and vulnerable and that’s what people are hungry for… To know they’re not alone and others are a few steps ahead of them and have tales to share from up ahead.”

The Times of Israel asked the Riegels about their thoughts on some pressing issues related to mental health. The following is an edited version of the conversation.

There is still such a stigma related to talking openly about mental health. Do you encounter this in your efforts, and what do you think can be done about it?

Sophie: I have been working on a couple of projects here at Duke about how the way we speak about mental health contributes significantly to this stigma. Medical forms ask about “problems” when it comes to mental health, but not about physical health. I think that the language stigmatizing mental health has been normalized in society and we need to bring it to light to show the impact it has on those with mental illnesses. There is less stigma because of celebrities coming out about their struggles, but there will always be stigma. I’m going to try to fight it, but I know I will never be able to fight it alone. Getting more people to fight with me is how we can do it.

Many mental illnesses are “invisible,” which makes it hard for people to recognize them and sympathize with those suffering.

Sophie: There were so many stereotypes about OCD that I didn’t necessarily fit that it made it hard for people to understand that I still had this illness without showing these very obvious and stereotypical signs. When I was in high school people knew me as this high achieving, All-American athlete, so they had trouble believing that with all these accomplishments there was something underneath that was going on. I think it was challenging to grasp the idea that I was able to succeed, but I was also really struggling at the same time.

Sophie Riegel was an All-American race walker in high school. (courtesy)

Sophie, you wrote that you wished your parents and doctors had offered you the option of taking medication for your anxiety earlier than they did.

Sophie: I had a fear that medication would get rid of my motivation and I therefore wouldn’t succeed anymore, but it turned out not to be the case and I would have benefited from starting on it earlier.

For me there is no stigma surrounding medication. Often when I am speaking, I get the question, “What if my kid wants medication but I don’t feel comfortable with it?” I think parents are really scared of any chemical intervention. The way I talk to them about it is I say, “If your kid had cancer, would you stop them from having chemotherapy because you were scared of it?” I also talk about how much medication has helped me so they understand that their kid could benefit in the same way.

Deborah, I am assuming that you were on medication yourself, but that you were worried about putting your child on it.

I am entitled to be in less pain and I should probably do something about it

Deborah: It was actually the other way around. I was not on medication and was a high functioning, high achieving person. I had considered medication and had similar concerns to Sophie, which we had not articulated to each other. I was afraid that medication could take away what makes me “me,” and makes me driven and successful. It wasn’t until after Sophie got medication that she and one of my very good friends had an intervention with me. I finally realized that even though my anxiety shows up differently than Sophie’s, I am entitled to be in less pain and I should probably do something about it — and I did. This is a chemical, neurological issue and that I needed to take care of like any other medical condition. I am so glad I did it. It’s been life changing.

How much do you think that the demands of today’s society contribute to the high rates of anxiety?

Sophie: American culture is constant go-go-go. I think that’s a huge part of it. There is no acknowledgement for how important it is to have down time. On social media you see people doing something all the time, and you think to yourself, how can I be sitting in bed doing nothing while these people are out there having a great time with friends, or accomplishing great things or working really hard — even though that’s kind of a façade and not the way that people really live their lives. That is a huge cause of all of this. There is also so much pressure on getting into a good college and there is more competition, people are more stressed out than ever. Once you are in college, the stress doesn’t end because you are trying to get into internships and then into the work force. One in five college students will consider suicide, which is unbelievable.

Sophie Riegel is a competitive track and field athlete. (courtesy)

So how do you handle this pressure?

Sophie: I will prioritize things that are really important to me. I decide that other things are not worth the mental energy and putting my mental health at risk. Learning to say no to things is hugely important, especially in college. Also, I haven’t really felt stressed in college because I dealt with so much stress before. Right now I am helping my friends cope with the stress because I learned those strategies early on due to having anxiety disorders.

Stress is a major issue in the workplace, as well.

Deborah: Stress and anxiety in working environments are expected. There are healthy levels of stress that help us achieve set goals and help us prioritize and make really good decisions. When stress and anxiety moves from functional to dysfunctional it can impact you physically, psychologically and in terms or your relationships. We shouldn’t wear “I’m so stressed” or “I’m so busy” as a badge of honor.

The research shows that women are twice as likely to suffer from anxiety and ruminate more than men

The research shows that women are twice as likely to suffer from anxiety and ruminate more than men. Women traditionally have more demands put on them than men do. Often they are working, caring for children, and caring for aging parents — all while trying to figure out how to eat well, exercise well, and take care of their own medical and mental needs in addition to those of the whole family. They are managing all of that while trying to think about how asking for time off or a flexible schedule might impact their career path and reputation.

Women often have a very high threshold for pain, including mental pain and it is not registering for them that they are anxious, stressed, burned out. It can persist and become worse when women don’t ask for or get help sooner. This needs to change individually and systemically — including with men.

What do you think are some major barriers to getting good mental healthcare within the current American healthcare system?

Sophie: There needs to be a change on the federal level to get healthcare to change or insurance companies to change their policies. I don’t have much control over that, but I do have more control over creating local resources for people who can’t afford going to a therapist or a psychiatrist.

Deborah: Historically, when lower income families — which disproportionately includes people of color — have considered seeking mental health treatment, there is often a fear that by asking for help you might lose your kids or job. There are systemic and institutional threats that I as an upper middle class white person do not need to think about.

Also, the more marginalized you are the less likely you will be able to find a mental health professional who looks like you, feels like you, and will be able to understand where you are coming from without your having to code shift or explain. For example, if you identify as [gender] non-binary and that feels like a really important part of your identity, it may be very hard — if not impossible — to find a non-binary mental health professional.

Sophie Riegel presents at a UJA-Federation of New York event. (Courtesy)

Where do you think the Jewish community is in terms of honestly and actively addressing mental health issues?

Deborah: My experience has been that the Jewish community is a reflection of the greater community. You run the range of people who feel like it’s personal and private, that would be invasive to talk about it for fear that it could negatively impact their families and careers. And there are people and organizations who are bringing it to the forefront and recognizing that not talking about it doesn’t make it not exist, and actually stigmatizes it further. We are finding people are being more and more willing to engage in the conversation.

What is your most important message to people with anxiety and other mental illnesses?

Sophie: Success and mental illness are not mutually exclusive.

Deborah: You don’t have to suffer.