New programs were beginning to address the traumatic foundation of Humboldt’s health problems. Then came COVID.

By Iridian Casarez iridian@northcoastjournal.com

Mary Ann Hansen probably understands the landscape of early childhood education in Humboldt County better than most. Before she became the director of First 5 Humboldt in 2015, she worked as a full-time lecturer in the Child Development Department at Humboldt State University and had been the head preschool teacher at the university’s child development lab.

Her career centered on helping train future teachers, social workers and caregivers to work with young children in a responsive way, based on the best practices and the most recent science. She taught the concepts of risk and resilience, and how they’re impacted by factors like poverty, parental substance use disorder, child abuse and other adversities.

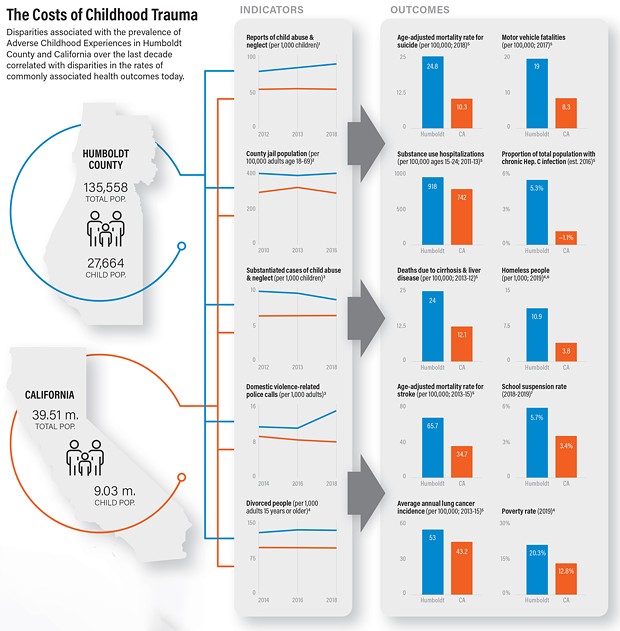

Hansen also grew up in Humboldt County and her passion for helping families overcome adversity is deeply personal. She’s seen the impact trauma has on families, neighborhoods and the entire community, and felt the stress daily in her pre-school classrooms, where children would overreact to minor situations because their stress response systems had become overwhelmed. And she knew the statistics — that Humboldt County has the highest rate of students receiving special education services (17.2 percent) in the state, a child abuse and neglect report rate 60 percent higher than the state average and a suspension rate 1.5 times the rest of California.

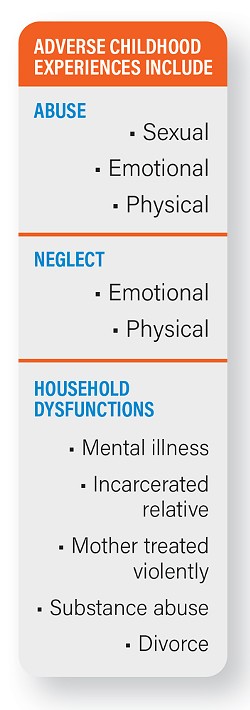

In 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente took a landmark step toward quantifying the amount of trauma a person experiences in their childhood, defining Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) as falling into one of 10 categories: sexual, emotional and physical abuse; emotional or physical neglect; and living in a household with someone who suffers from mental illness, domestic violence, substance abuse or divorce, or having an incarcerated relative. Each experience counts as one ACE, with the total representing an ACEs score on a scale of one to 10.

Hansen herself had a score of eight. She understood the science and impacts of stress, childhood trauma and the phenomenon of resilience — the ability to cope with tough situations. But she still didn’t fully comprehend the depths to which childhood trauma was impacting just about every aspect of life in Humboldt County.

That was, until she heard a 2015 lecture by Nadine Burke Harris, now California’s first surgeon general, about her Center for Youth Wellness’ (CYW) 2014 study on ACEs and how traumatic experiences affect children long term.

“When I first heard Nadine Burke Harris present on ACEs in California, I felt like a light bulb came on and all the pieces started fitting together,” she says.

A Generational Cycle

While it was evident that too many Humboldt County children were experiencing trauma, the CYW study quantified it, finding Humboldt and Mendocino counties combined to have the highest rate of adverse childhood experiences scores in California, with about 75 percent of residents having experienced one or more of these childhood traumas. That far outpaces trauma rates in other areas, like Los Angeles County, where 61 percent of residents had experienced one or more ACEs, or the 53 percent of Santa Clara County residents who had an ACEs score of one or higher.

But more troubling was the study’s finding that 30 percent of Humboldt and Mendocino residents have experienced four or more ACEs.

That was a turning point for Hansen, as there was now an official report showing Humboldt County residents suffer from more trauma than their counterparts in other counties. In that sense, the study corroborated what Hansen had been seeing.

But the study didn’t just quantify childhood trauma, it also found that having a high ACEs score correlated with negative health and behavioral outcomes in adulthood.

“A person with four or more ACEs is 5.13 times as likely to suffer from depression, 2.42 times as likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), 2.93 times as likely to smoke and 3.23 times as likely to binge drink,” the CYW report states.

The study’s findings suggest that some of Humboldt County’s most entrenched problems — from rates of drug and alcohol addiction to homelessness and crime — may take root in childhood trauma. And the reasons for that may be biological.

- Graphic by Jonathan Webster / North Coast Journal 2020

- Sources: Webster, D., et al. California Child Welfare Indicators Project Reports, UC Berkeley Center for Social Services Research; 2California Sentencing Institute; 3kidsdata.org; 4U.S. Census Bureau; 52018 Humboldt County Community Health Assessment; 6Humboldt Housing and Homeless Coalition Press Release Feb. 20, 2019; 7California Department of Education.

Many poor health outcomes, the study explains, stem from a chemical imbalance of cortisol, the stress hormone produced in the adrenal glands that some refer to as the body’s alarm system. When someone is exposed to a stressful situation, their bodies begin to release cortisol, which activates a fight or flight response, a crucial defense mechanism that has enabled humans to survive throughout evolution. But when people are constantly exposed to these stressful situations, releasing more and more cortisol, the hormone becomes a toxin that can affect the body’s immune system and, in children, brain architecture.

“I saw, during my years as a preschool teacher, the clear link between a family’s stress/risk factors and a child’s ability to manage stress and navigate a preschool classroom’s challenges,” Hansen says, adding that toxic stress can manifest in behaviors commonly diagnosed as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. “Being on alert because of an activated nervous system makes it hard to sustain attention during circle time or read the good intent of another child who wants to play with their blocks, causing them to ‘overreact’ when the circumstances test their ability to stay calm. What has helped a child navigate an unsafe environment becomes a liability in the classroom.”

The CYW study builds upon another published in the American Academy of Pediatrics that found toxic stress can lead to potentially permanent changes in a child’s ability to learn cognitive, language and social-emotional skills, hamper their ability to deal with adversity and cause physiological changes that can lead to higher rates of stress-related chronic disease and unhealthy lifestyles. In short, childhood trauma can lead to widening health disparities later in life.

That was another connection Hansen began to see clearly. On top of feeling a sense of validation that county residents were experiencing higher rates of childhood trauma, she also began to see how that could explain poor health and behavioral outcomes, in some cases creating a generational cycle of trauma.

According to the 2018 Humboldt County Community Health Assessment, local health outcomes are worse than the state average by most measures. Humboldt County also sees rates of deaths related to liver disease and cirrhosis, the most common causes of which are chronic alcoholism and hepatitis, that are twice the state average. Local lung cancer rates outpace the state average, while local youth report higher rates of binge drinking than their peers statewide and 18.3 percent of local residents smoke tabacco compared ot 11.6 of Californians. From 2013 through 2015, Humboldt County saw nearly 50 percent more COPD deaths per capita than the rest of the state.

“I grew up in Humboldt, and my heart is in this community,” Hansen says. “Suddenly, the struggles and resilience of Humboldt’s families made more sense. It was an ‘aha’ moment tinged with sadness because of what it means for so many of our residents to have one or more ACEs, but also tinged with hope because understanding helps healing.”

‘That One Person’

However daunting the correlation, ACEs experts like Hansen, Harris and Humboldt Independent Practice Association Medical Director Candy Stockton also know it is not causation and having a high ACE score doesn’t necessarily predetermine an adulthood filled with poor health outcomes and behaviors. There’s hope for children to overcome trauma to grow up happy and healthy like Hansen, who credits people outside her home with helping her overcome an ACEs score of eight to live a healthy life.

“I personally grew up with ACEs in my life and I was really lucky to have mentors and teachers who believed in me,” she says. “When I went to college I was lucky enough to have a mentor whose study was resilience … and what she found was that the difference between being successful and happy in your life [with ACEs] was whether or not you had that one person when you were growing up who believed in you and believed in your potential. And I think that’s a really powerful message.”

Positive relationships like these can help children develop support systems and healthy habits, like eating well, exercising and taking care of their mental health, all of which help build support systems and the resilience necessary for people to cope with adversity.

“Providing that connection and that support and the buffering as families experience stress is the key to keeping stress from becoming toxic, and becoming something that turns someone’s stress system on for their whole life,” Hansen says.

With all of these new understandings of how ACEs impact children, Hansen knew that building a healthier community needed a communitywide approach, so she went to the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors and asked the county to invest in ACEs prevention and child mental health. The board agreed, allocating a portion of marijuana cultivation tax revenue toward maintaining and improving county mental health services for children and families. Many Humboldt County community organizations and schools, meanwhile, have begun offering new programs and changed old-fashioned systems, all with an eye toward trauma-informed approaches.

“If we can help stabilize kids’ lives now, then they’re less likely to develop those serious and persistent medical and mental health issues later in life,” Stockton says.

Humboldt County schools have implemented a new training framework aimed at helping school staff become more nurturing, trauma-informed and responsive. The focus is on emotional wellness and inclusive discipline practices, putting a premium on relationships and ensuring that students feel seen and heard. The goal is to support students’ social-emotional learning with schoolwide systems and disciplinary approaches that are reflective rather than reactive.

This new approach has had impacts throughout the county, from specific initiatives (like Klamath Trinity School District creating a student wellness center for school children in the Hoopa Valley) to countywide programs (like the county Department of Health and Human Services partnering with the county Office of Education to streamline the delivery of mental health services for students).

But the boldest steps are happening in the McKinleyville Union Elementary School District, which partnered with the Humboldt Independent Practice Association to create a school-based health center on the McKinleyville Middle School campus. There, led by Vanessa Vrtiak, another Humboldt County native with ACEs in her past, a network of innovative peer support groups are connecting kids to one another and a unique collection of mentors, many of whom have walked in their shoes.

Vrtiak’s vision for the program took root partly in her childhood and her belief that it was the teachers who believed in her, cared for her and guided her that made all the difference.

“I see myself in those kids and I know the protective factors that they need to stop that trajectory of entering the criminal justice system or just numbing themselves from not feeling the pain of their childhood is showing them love and support and care,” she says. “And that was what saved me — is I always had teachers that loved and cared about me every step of the way. Always. I know that we can’t ‘save’ these kids, nor do I really like that term, or want to. But I know that we can show them another way and that way is always through love and just seeing them.”

- Submitted

- A virtual group photo of the volunteer mentors of the Humboldt Independent Practice Association’s Boys to Men group, which piloted at McKinleyville Middle School last year before expanding to multiple campuses for this school year.

Boys to Men

Roberto Gomez, in many ways, is an unlikely candidate to be that proverbial one person in a student’s life. Growing up in Humboldt County, he experienced all 10 traumas outlined by the Centers for Disease Control and Kaiser Permanente.

After Gomez’ father was incarcerated, he saw his mother become the victim of domestic violence at the hands of his stepfather. Then, when he intervened, his stepfather physically abused him. But Gomez says it was only after his mom went to prison when he was 10 years old that he truly felt alone. He then went to live with his aunt but she was working three jobs trying to support him and his three sisters and he began to feel physically and emotionally neglected. So, he says. he started hanging out with the wrong crowd looking for acceptance, leading to a path of self-destructive behavior.

“All I wanted was attention — someone to care for me — and I searched for that in the streets and it didn’t get me anywhere good,” he says.

Gomez went on to be incarcerated 38 times in a span of 15 years, his first arrest coming at age 12 and the last at 27, which led to a moment of clarity and a decision that he was tired of coming back to the jail, tired of hurting his mom and his sisters.

When Vrtiak asked Gomez to be one of the very first guest speakers for a Boys to Men group she was putting together at McKinleyville Middle School, he jumped at the chance. The group provides a safe space for young boys to be open about their feelings, redefine what it means to be called “a man” and learn how to take care of their mental health and well-being without the fear peers will be judgmental, all with the help of volunteer mentors and positive figures to guide them.

Gomez says he wanted to help students avoid making the same mistakes he made, to be the mentor he never had.

“A lot of the kids in the county lack a positive figure in their lives,” he says. “They don’t know how to reach out when they need help and boys are often taught that they can’t be weak or they can’t be vulnerable, that violence is OK. So what happens is that they can’t talk about their feelings and they learn to numb themselves with drugs, and the behavior progresses, leading to incarceration. I have done a lot of research on the ACEs score and [the Boys to Men Group] is the first step that I see in actually engaging with this mission of helping kids with high ACEs.

The group met at lunchtime. Gomez was just one of a diverse collection of guest mentors invited by Vrtiak — a Eureka police officer, a poet, a journalist and activist, educators and a father — each with a story to share about finding their voice and identity. They talked about respecting women, learning self-care through wellness practices, standing up against bullying and for inclusivity. They detailed how they could have taken different paths in life and broken down the boxes of toxic masculinity, while talking openly with students about how they hold themselves now.

“We all need guidance,” Vrtiak says, “and I think there’s this misconception that men are naturally violent and I think what’s happening in this group is that these kids are pushing back against this misconception of what it means to be a man. A lot of the students are processing these different ideas of how to carry themselves.”

Kintay Johnson, the director of special programs at College of the Redwoods, is from Pensacola, Florida, but has lived in Humboldt County since 2003 and spoke to the group last spring. Johnson says it’s important for kids to have influential people in their lives, even if just for a moment, to plant a seed in their mind and show them what’s possible. He spoke to the group about the power of words and how they can be used to diffuse any situation, about being mindful and finding non-violent ways to communicate.

“I talked to them about keeping your cool and trying to make positive choices and not head down a path of self-destruction, and I gave them some examples of the things kids in the same age as the group are doing down from where I’m from — where they are making life-changing decisions that they can’t come back from,” Johnson says.

Just like Gomez, Johnson wants to help students choose a path of resiliency.

And it’s working, Vrtiak says, describing how a school administrator told her about the time one of her boys group students came into the office after directing foul language at another student. When the administrator asked what Gomez and the other mentors would tell him, he responded remorsefully, saying Gomez would have guided him to do better.

After a couple of the Boys to Men group sessions, Vrtiak (who doesn’t sit in on the groups, wanting to give students privacy) decided to survey students about the group. The responses were fascinating.

“A lot of students reported feeling a deeper connection with their community,” she says. “They talked a lot about treating their teachers with respect and learned how to communicate with their teachers and adults. A lot of them don’t know how to advocate for themselves, so a lot of them reported feeling an increased sense of confidence and self-worth and felt like they wanted to be a mentor to youth themselves.”

‘Everyone Needs Support’

Before she signed on as the program director for McKinleyville Middle School’s health center in 2019, Vrtiak worked at the Humboldt County jail developing rehabilitation programs for incarcerated men and women. But after a couple of years, she decided she wanted to reach people earlier — before they’d made potentially life-altering mistakes.

“I worked with so many young men and women while they were incarcerated and couldn’t help but think what their lives would be like if they would have had support in their developing years,” says Vrtiak.

One of Vrtiak’s first steps after arriving at McKinleyville Middle School was organizing a peer health education group. It was a failure as, much to her dismay, no students showed up. But the answer proved simple. She asked students what kinds of support groups they wanted to attend and learned they were looking for specific groups tailored for boys, girls and those who don’t identify with those genders.

So the health center followed the students’ lead and began creating voluntary open spaces for students last year — a girl’s group, an LGBTQ+ group and the Boys to Men group. Although each has been impactful in its own ways, the Boys to Men group became the one Vrtiak is most proud of. But it’s only one prong of McKinleyville Middle’s approach.

McKinleyville Middle School’s health center is also designed to mitigate student absenteeism and foster emotional growth, giving students access to a health center where they can get minor healthcare services and well-being support without missing school.

“It’s not a traditional school-based health center in the sense that it’s like a full spectrum health care center,” says Stockton, explaining that while the center does offer health services, its focus is more on empowering students and enriching their lives. “So, a lot of mental health and emotional support services and connections with community resources that are needed, like food, housing, parenting support, those types of resources.”

There’s more than anecdotal evidence and testimonials to suggest the multi-pronged program is working.

According to data from the California Department of Education, 8 percent of students at McKinleyville Middle School were suspended at least once in the 2018-2019 school year, including 91 for violent incidents. While that’s a 5-percent drop from 2017-2018, it’s still more than double the statewide suspension rate of 3.4 percent.

In an email to the Journal, McKinleyville Middle School Principal Elwira Salata said that in the 2019-2020 school year (which included the distance learning after COVID-19 hit Humboldt County), about 41 students were suspended, which would be a more than 50-percent decrease from the prior year and a potential sign that Vrtiak’s groups are having an impact.

Countywide, suspension rates are 60 percent higher than the state average, though they aren’t dispersed evenly throughout the county’s 30-plus school districts. In 2018-2019, Humboldt County had a suspension rate of 5.7 percent but that jumped to 10.1 percent in the Southern Humboldt Joint Unified School District, 12.9 percent at Fortuna Union High School, 17.3 percent at Klamath-Trinity Joint Unified and 23.7 percent — the county’s highest and seven times the state average — at Loleta Elementary.

Although school suspensions are still higher than the state average — and much higher, in some cases — new wellness initiatives and a focus on trauma-informed practices are working, officials say, and suspension rates are declining overall.

Gomez and Johnson believe the type of mentorship program piloted at McKinleyville Middle School — teaching communication skills and mindfulness, while giving students access to a diverse group of positive role models — would benefit students in all Humboldt County schools.

“If they have positive male or female role models in their lives to teach them how to deal with challenges and adversity, to develop resilience, if we can teach young people that, that’s one of the most amazing gifts ever that we can pass onto the next generation, is how to be resilient,” Johnson says. “To teach them that when a challenge is thrown your way, when something is difficult, that it’s not the end.”

But it’s not just schools recognizing the importance of ACEs and trauma-informed practices.

Since being sworn in as California’s first surgeon general in February of 2019, Harris has made ACEs one of the key focuses of the office. Wanting to improve health outcomes and break the cycle of intergenerational trauma, Harris created the ACEs Aware initiative with the help of the state Department of Health Care Services.

The initiative’s main goal is to help doctors screen for ACEs, recognizing they are an important factor in determining who is at increased health risk due to toxic stress. Once patients are screened, doctors can give them information on community resources, like housing assistance and food stamps, and talk to them about the importance of managing stress to stay healthy. If a patient is at an extremely high risk of poor health outcomes, they are referred to a mental health specialist, though the American Association for the Advancement of Science reported some critics of Harris’ initiative worry California doesn’t have enough of these specialists to meet the demand that will possibly stem from mandatory screenings.

Hansen, however, says there are many effective interventions that can be applied before referring patients to specialists.

“It’s talking about connecting and supporting your child,” she said. “It’s talking about mindfulness techniques. It’s about getting exercise. I mean, there are all these things. It doesn’t have to cost us a lot. It’s about having a trauma-responsive practice, whether that’s as a clinician, a teacher or a doctor. But it doesn’t always mean you have to refer out to other more costly resources. Sometimes the solution is listening and helping put tools in people’s hands.”

Having seen some of these changes in McKinleyville, Vrtiak says she knew other students could benefit from the added layers of support and decided to expand the group.

Through grant funding secured by the Humboldt Independent Practice Association, the Boys to Men group will be expanding this year to McKinleyville High School, Humboldt County Office of Education’s Court and Community School and Humboldt County juvenile hall. The Court and Community School is for students who can’t attend a traditional public school — those who are on probation, were suspended multiple times or have issues with substance use. Often, they have high ACEs scores.

Gomez, who spent time in both juvenile hall and HCOE’s Court and Community School, says he’s excited about the expansion, saying it’s especially important for young students who have already been stigmatized as criminals to have access to these programs.

“Everyone needs support,” Gomez says. “There’s this stigma about how people who are incarcerated are criminals but they don’t know what got them there. … These are innocent babies that grow up in a messed-up life that, next thing you know, are going down these destructive paths.”

The 11th ACE

When the novel coronavirus pandemic hit Humboldt County in March, closing schools and businesses, leaving people in their homes, some unemployed and out of school without anywhere to go, Vrtiak knew some of her students lost their outlets of support and others were trapped in increasingly unhealthy, stressful situations.

She was especially worried about the students who extensively utilized the health center and were chronically absent, so she did what she would have wanted her teachers to do in the face of a pandemic: She began visiting students at their homes to check in and see what they needed, if they had enough food, or if their families needed information about applying for unemployment benefits or other forms of assistance.

Vrtiak felt it was important to do this because in Humboldt County — where child abuse, neglect, substance abuse and poverty rates are already higher than the state average — the COVID-19 pandemic meant something else. Here, Hansen says, COVID-19 became an unofficial ACE, a new layer of trauma.

The pandemic layered stress onto already stressed households, closing businesses and putting people out of work, sending families scrambling to figure out how they were going to provide for their basic needs, like housing, healthcare and food. Some dug into their savings, many more filed for unemployment. (Humboldt County residents filed more than 5,846 unemployment claims in April compared to just 570 filed the same month a year prior.)

The U.S. Census reports that 20.8 percent of Humboldt County residents lived below the poverty line before COVID-19, with 58 percent of the county’s school children eligible to receive free and reduced lunches. According to the Humboldt County Office of Education, more than 1,400 local school children qualified as homeless last year.

“So there are the classic 10 ACEs but then there’s poverty and racism, bias, living in community violence — all of those things are like the second realm of ACEs that cause the same physiological formula of toxic stress that turns on someone’s stress system,” Hansen says, “[The pandemic] isn’t an identified ACE but it has the same effect.”

In a webinar for the ACEs Aware initiative, Devika Bhushan, a pediatrician and chief health officer for the Office of the California Surgeon General, said we may see the similar long-term health effects from COVID-19 as from prior infectious disease outbreaks, natural disasters and economic downturns, including increased rates of heart attacks, stroke, diabetes, COPD, asthma flares and mental health issues like depression, anxiety, suicidality and post traumatic stress disorder.

According to Bhushan, almost everyone is feeling acute toxic stress from the pandemic, whether it stems from the risk of getting COVID, grief and loss, economic strain or widespread social disruption from distancing and isolation measures meant to prevent the virus’ spread.

She’s not wrong, Vrtiak says, noting that when she started visiting families last spring she saw a common theme. Many were feeling anxiety, depression and a lack of motivation, she says, adding that while some students were anxious to get back to school, others were really scared of returning because their parents had underlying health issues and were at increased risk from the virus.

Hansen adds that for people and children with ACEs in their lives — who were already vulnerable and learning to manage stress from various sources — the COVID-19 pandemic just adds to that burden, exacerbating what they were already experiencing.

“For COVID, the isolation is really hard for families,” she says. “But if you’re a child who is experiencing child abuse in your home, then it also — in most cases — means that you’re isolated from the teachers that might be the buffer in your life or the one who’s keeping an eye out when they think something’s up, or call [Child Welfare Services] when they feel necessary.”

In an email to the Journal, CWS Deputy Director Ivy Breen says prior to the pandemic, CWS was receiving an average of 270 total child abuse and neglect referrals per month, with an average of 50 coming from school staff and teachers. Between April and August, that number dropped to 206 a month — a 24 percent reduction. (She says CWS has seen an increase in reports since the start of this school year, even though most schools have begun with distance learning.)

‘Showing Up’

The array of new programs and approaches Humboldt County organizations have implemented to help children be resilient in the face of trauma and toxic stress centered around personal interaction — small group discussions, mindfulness lessons, safe spaces. But when Humboldt County Health Officer Teresa Frankovich issued a stay-at-home order last March, that all had to stop.

The systems of support designed to combat isolation — to make students feel seen and supported and cared for — broke down under the strain of the virus.

“So at the same time that this pandemic is increasing the risk of ACEs and other toxic stressors, it’s decreasing the conditions that we need to act as buffering sources to prevent the onset of toxic stress,” Bhushan says in the webinar.

While there’s nothing that can replace the safety net that physically attending school provides thousands of local children or the specialized services that can be provided on campus, Vrtiak and the other Humboldt organizations realized their work was more important than ever, and would have to adapt.

First 5 Humboldt, which offers trauma-informed training, playgroups and parenting classes, among other things, closed most of its classes but began offering online services, like one-on-one consultations between families and early childhood mental health specialists, and virtual parenting circles, where parents can get together online with and talk.

First 5 also continued connecting families to resources and webinars related to stress, as well as self-care strategies, while offering trainings on the “community resilience model,” which teaches people how to recognize their own stress triggers and what tools they can use to manage their responses.

Humboldt Bridges to Success, a new partnership between DHHS and the Humboldt County Office of Education, focused on streamlining mental health and learning support services for local students, worked to ensure the families it helps have what they need to adjust to the realities of the pandemic. It mobilized to support online learning and support services by getting students access to computers, internet service, technology and tech support, while also connecting families with nutritional assistance and other safety net services.

“Families were really kind of in a state of shock initially,” says Julie Beach, the county supervising clinician for the Bridges program. “And so we just wanted to really make sure that they were able to access education and counseling through telehealth and access the resources for Calfresh, unemployment benefits and Medi-Cal.”

Vrtiak says that’s also a huge part of what she was doing — making sure the families she was visiting had the right means to access resources. Mentors from the Boys to Men group helped her visit students and deliver food, as well.

During the summer, Vrtiak had to think about how the health center would continue to offer wellness support groups in ways that could follow physical distancing guidelines and avoid gatherings. Online was the only option.

The boy’s group will start in mid-October online but with the same format — a mentor presenting his story and giving advice, with time for questions and a brief check-in. Even though they can’t continue the kind of in-person conversation that adds an extra layer of connection, Vrtiak says the thing that matters most is the commitment of the group mentors to continue showing up and helping these kids. Even through a pandemic, these mentors are continuing to be the positive people that Hansen says can make a difference in leading a child with adversities to become a happy and healthy adult.

“That’s what’s so cool about this group,” she says. “We teach them those protective factors. We talk to them about self-care and wellness. … But what matters most is that the male mentors are showing up and listening to and loving these kids. That’s what matters most.”

But asked to imagine how a similar pandemic would have impacted their childhoods and their ability to cope with other ACEs, both Gomez and Vrtiak said they needed some time to gather their thoughts and reflect. Their responses ultimately bring the stakes of intervention efforts in the time of COVID into stark relief.

Gomez says his family is primarily Spanish speaking and, without any Spanish news outlets available, doesn’t watch the news. His mother is a frontline worker and he says she likely would have been exposed to COVID-19, adding yet another stressor. He says he probably would have still been hanging out with a bad group and would’ve tested positive for the virus.

Vrtiak, meanwhile, says her mother would have lost her job as a hairdresser, leading them to lose their home and become homeless once again. Her mom also wasn’t tech savvy, so the pandemic and distance learning would have put a halt to Vrtiak’s education, removing her only supportive environment.

“School was the place where I got to be a kid, where I felt safe and special,” she says. “COVID would have completely transformed me as a person.”

Iridian Casarez wrote this story while participating in the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism’s 2020 California Fellowship.

Iridian Casarez (she/her) is a Journal staff writer. Reach her at 442-1400, extension 317, or iridian@northcoastjournal.com. Follow her on Twitter @IridianCasarez.