Editor’s Note: This is the eighth and final story in a series produced by Granite State News Collaborative that takes a look at how school districts across the state responded to the challenges of remote learning and plans for improvements in the fall

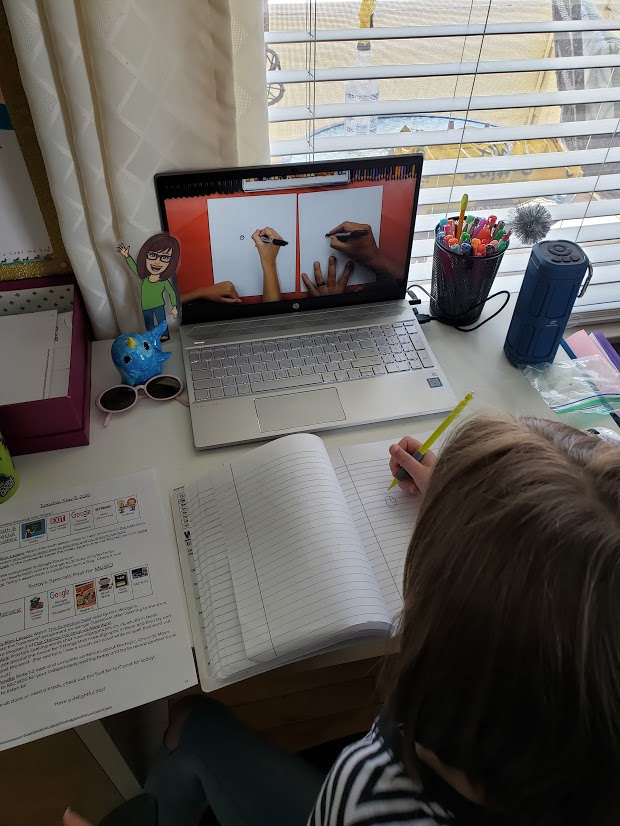

Teaching her third- and fourth-grade students at Jennie Blake Elementary School in Hill, New Hampshire, by video conference last spring, teacher Alicia Schaefer spotted a trend.

“I started to notice that some of my really good students are really social, and they were the ones that seemed to have the hardest time,” Schaefer said. Learning remotely, some of her most gregarious students became listless without the chance to interact with their peers in person.

“Even though they were still doing their work, they just didn’t seem like the same students,” Schaefer said.

She and the paraprofessional in her class responded by trying to create or maintain opportunities for personal connection, “instead of making it about academics all the time,” Schaefer said. They started holding “lunch bunches,” inviting students to have lunch with them over video and “just chat.” Every Friday, as they would have in the normal school atmosphere, they held a closing circle to talk about what went well during the week and what they were looking forward to in their weekend.

“One student asked my para if they could work together and look at the flowers growing in her yard,” Schaefer said. The teaching assistant would tag along by video as the student explored the land outside her house.

This type of attention to students’ social and emotional wellbeing became vital for students of all ages and abilities last spring, after Gov. Chris Sununu ordered all public school buildings to close in mid-March to protect communities from the coronavirus pandemic. Reporting for the Granite State News Collaborative’s “Remote Learning Progress Report” shows that, as this need surfaced, some educators and school administrators got very creative in response — and got to know a lot more about their students’ families in the process.

“We have always been concerned about student’s mental health, even before [COVID-19].” Dan LeGallo of the Franklin school district said about the resources that the department has for students, adding that the funds for these services were given through a grant.

The district monitored the level of engagement that students were having with their classes and teachers, LeGallo said. In mid-May, the school counselors started reaching out to families of students that they thought were less engaged than other students, which was determined by the school work that they passed in or their online participation.

This practice was done by most districts in the area, including SAU 58, comprised of Northumberland, Stark and Stratford, where Ronna Cadarette is superintendent.

“We have worked with North Country Educational Services to get additional guidance support for families that may need emotional support,” Cadarette said, adding that children feed off social and emotional support from their parents. “We reached out to families and students to see how they were doing.”

Safer at home, but not always

Being in school and learning in person is a way for students to not only become educated, but engage in social interactions with their peers, and get away from hardships that they may be facing at home.

In SAU 13’s end of the year survey that was open to elementary, middle and high school students in Madison, Freedom and Tamworth, the general consensus was that students miss the interaction of having in-person classes.

“I think that in a society as a whole, we are in crisis mode,” Meredith Nadeau said. “We are redefining what normal looks like in this and post-COVID world… children are isolated and facing it on their own. Their social networks and routines have been impacted and no one has been able to answer for them when and if those things are going back to normal.”

Nadeau’s district has counselors in place to help students during the transition. They may sit in on classes to see how students are doing, and check in with those through phone calls that they know may be having a more difficult time.

School counselors would ride the school buses during meal drop off, too, to get an idea of how things are going for families.

“No matter what resources are available in a household, living months on end like this, we aren’t used to it,” she said. “The level of stress and anxiety in the climate has been overwhelming for everyone.”

Students may feel the added stress from parents that may be experiencing layoffs due to the pandemic, or other financial hardships, Nadeau said.

She added that where some kids are at home more, they may be experiencing domestic violence or mental health issues and are unable to check in with students in-person like teachers normally would have to keep track of their student’s well-being. Teachers across the districts have noted the students that haven’t shown up or participated in remote learning and have reached out to them.

According to a survey put out by The New Hampshire Department of Education that garnered nearly 42,000 responses from parents, a clear majority — 65 percent — said they felt their children’s well-being was prioritized by district and school leaders during remote instruction. However, just over half the responses reflected parents’ perception that their children’s stress levels had increased since transitioning to remote learning.

And opinions on whether schools had the resources to either identify or support their children’s health and social-emotional needs in a remote learning setting were evenly split: about one-third of responses agreed, one-third disagreed, and one-third were neutral on the topic.

“Our goal is to have kids back safely [in the fall] for a whole host of reasons,” Kevin Carpenter, principal of Kennett High School said. “In school they are more likely to get regular trips to the doctor, more likely to get their vaccines tracked through school. The number of reports going to the Division of Children, Youth and Families (DCYF) is going down and we don’t think the number of suspected events are down, we think it’s down because they can’t get out and report them.”

To help aid younger kids in the transition to online learning, kindergarten and younger grade teachers in SAU 39 (Amherst, Mount Vernon and Souhegan), split up class time into groups of five to help students engage more.

“Some elementary teachers scheduled time at night to read (over Zoom video conference) to kids at seven or eight before they went to bed,” Steel said. “They went above and beyond to make sure the kids felt connected.”

Keeping Meals Going

With kindergarten through grade 12 away from school and learning remotely from home, many are missing the only time that they are able to have breakfast and lunch.

Since the start of remote learning, New Hampshire has served 3.9 million meals to students under the age of 18 across the state, according to NH Department of Education data, and as of June 21, 22 SAUs were signed up to continue to provide meals to students through the summer.

Franklin school district has the second-highest rate of free and reduced lunch, according to Dan LeGallo, at 63 percent. According to data from Save The Children, which recently measured county-level child wellness across the country, Merrimack county has a child hunger rate of 11.1 percent.

To ensure that these students were still receiving their meals, the district gathered teachers and nurses aboard a bus to help pass out 900 bagged lunches along the bus routes to the families that needed them.

“We had five busses with the same bus routes and stops so students and families would know exactly where to go,” LeGallo said. “We got breakfast and lunch delivered to them and were able to feed all students and any student that wanted to get free breakfast and lunch. We did it through the end of the school year and ran the busses three hours a week to feed them.”

The Berlin school district, which is part of Coos county, has a child hunger rate of 15.4%. It had a similar strategy and was able to feed 600 students a day with ,1200 meals a day (breakfast and lunch), five days a week.

“We know that we are the main food source of food for many of our children in the community,” Julie King, the superintendent said. “In a typical school year, pre-COVID, we have an after school program and last year they added on dinners for students. Some students were eating three meals a day at school for 180 days.”

A local church was able to step up and provide meals for the students during the week after schools were moved to remote learning to give the district time to make a plan of action.

King said that the community stepped up and teachers volunteered their time to help with handing out meals. They never once had to ask for extra help, she said, adding that some professionals in the community also helped.

Wellness Wednesdays

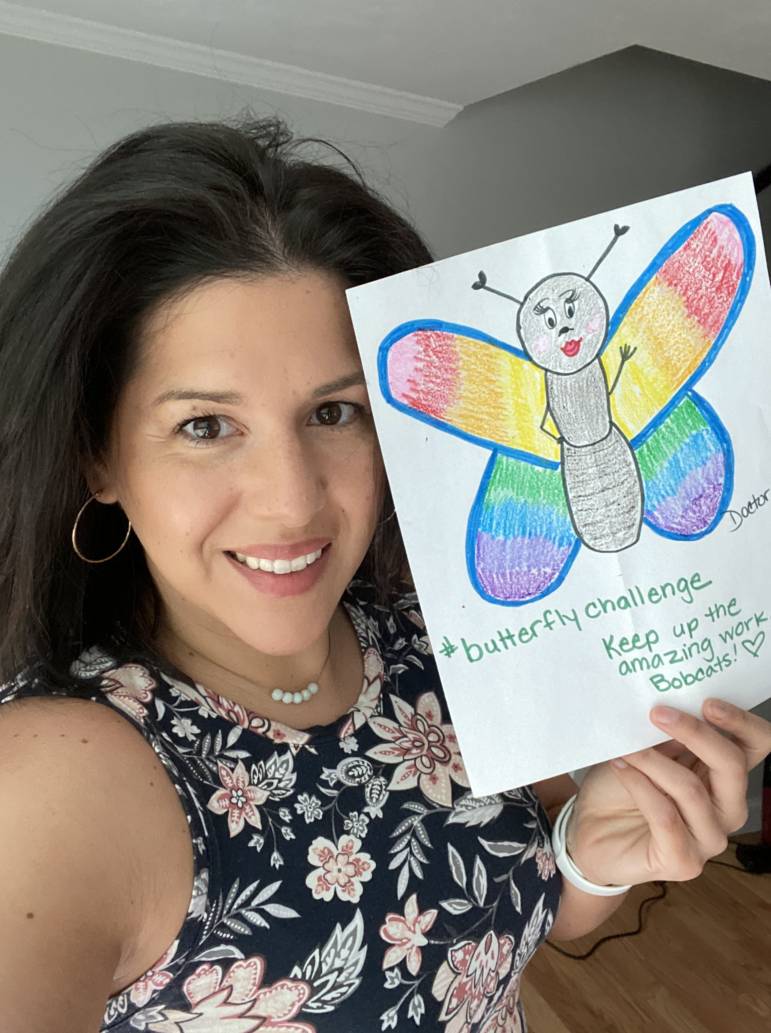

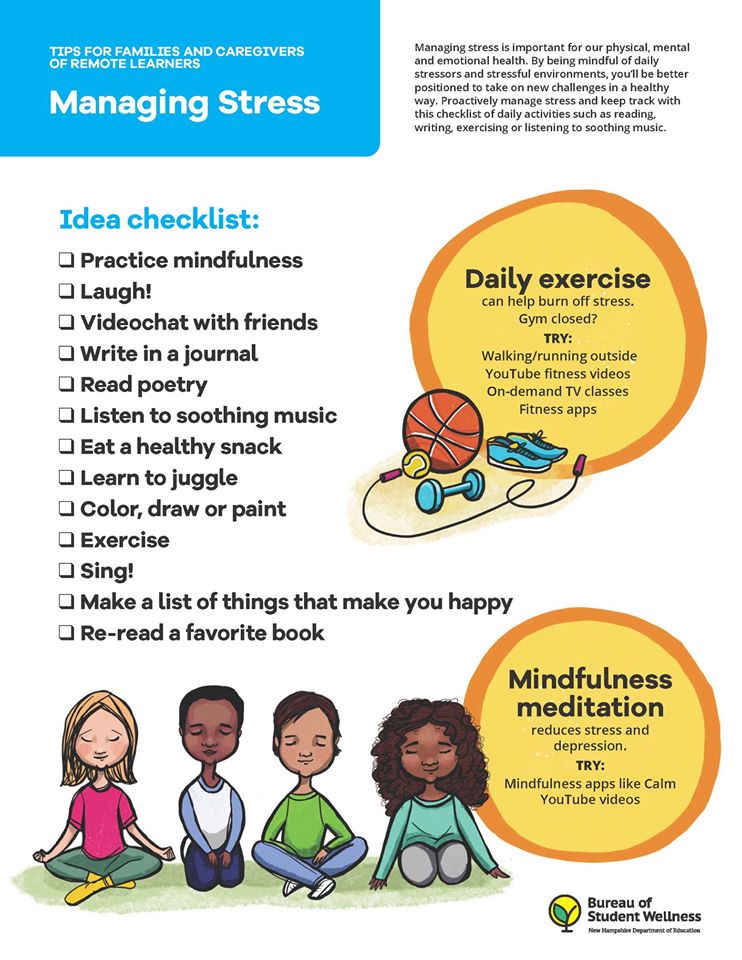

Remote learning eliminated inherently social time that is built into normal school schedules: lunch, recess, interacting in the hallways between classes, waiting for the bus. Educators had to develop new structures to create that kind of shared experience. And given the anxiety-inducing bleakness of a global pandemic and the ensuing economic distress many families were experiencing, most of those new structures were built around self-care.

In Julie King’s school district, Berlin, Wednesdays were days to get kids up and moving.

“Teachers did a good job of incorporating activity into the curriculum,” King said. “They’d have dance party breaks, or challenges for the kids. Art teachers did challenges to go out in nature and build an artistic piece of work with nature materials. One Wednesday, I threw out a challenge to go out in the snow and build a snowman and we’d choose the best one. Once the weather turned nice, there was a challenge to pick up trash near their house.”

She adds that for younger elementary school children, their activities need to change every 10 to 15 minutes to make sure they are fully engaged.

The Wednesday breaks in the district proved to be great to get kids to maintain their social skills that they were missing from being away from school and as a way for them to slow down.

“Being in elementary school and having recess is so important for kids. Not only the physical activity, but learning how to work with other people,” she said. “Issues arise during recess, it’s known that kids bicker or fight over taking turns. It’s part of the learning process where they learn to have patience when they ask nicely and compromise — they’re skills adults need to properly function in this world.”

The trend was one that other school districts had their own versions of. Some used it as a “catch up day,” and others used it like the school district of Berlin did.

In Conway, at Kennett High School where Carpenter is principal, Wednesdays were used as a day where students could sign up for video classes to help them maintain their mental health or learn a skill. Kennett High is made up of eight surrounding towns.

Yoga classes, cooking classes and meditation were among the classes offered for the students to sign up for virtually. According to Carpenter, not as many students signed up as he would have liked, but it’s something that the school is planning on continuing in the fall if remote instruction resumes.

“We also had cell phone photography classes, coding, cooking and crossfit exercise classes,” he said. “Career talks with law enforcement, one in the mental health field with psychologists and social workers — we wanted to do activities for the kids that were remote and non-academic, but social for the kids.”

Adam Steel, the superintendent of SAU 39 (Amherst, Mount Vernon and Souhegan), said that moving forward, having counselors in place for students’ mental health among the transition is one of their top priorities.

The district hosted “Flex Days” for students — and teachers — to catch up. The goal was to not overwhelm students as they make the new transition, but to rather give them a day where they could count on having time to slow down.

He hopes that moving forward, remote learning can serve as a way to redesign their teaching model as a way to focus on kids’ individual needs.

In Berlin, they will have some social emotional learning in place, King said recently in an interview with NH PBS’s The State We’re In. She also said staff and students will continue to have access to local community agencies for counseling services, something they had pre-pandemic through grant funding.

“Emotionally as citizens, this has hit us hard. The fear and uncertainty, the not knowing what is going to happen,” she said. “I know ultimately children are resilient. So I’m hoping this is not a huge hurdle, a huge challenge for this generation. …We all just need to be watching out for one another and checking in often to make sure everyone is okay.”

Hilary Niles and Melanie Plenda contributed to this report

⇒ Click here for an overview of the series.

Part 1- Remote Learning Progress Report: Schools Contend With Myriad Challenges of Remote Instruction

Part 2 – Broadband proves to be an issue as schools across the state switch to remote learning

Part 4 – From large class sizes to cheating, educators look to improve remote learning instruction

Part 5 – Districts Had Trouble Tracking Student Progress Remotely:

Part 6 – Special Needs Students, Parents, Struggled During Remote Learning:

These articles are being shared by partners in The Granite State News Collaborative. For more information visit collaborativenh.org.