Advertisement

The Checkup

The American Academy of Pediatrics has a new policy statement on bariatric surgery for adolescents.

Dr. Sarah Armstrong has a 15-year-old patient who has been going to the weight management clinic at Duke since he was 8 years old.

“The parents both have worked with us tirelessly, the family drives an hour to see us, they’ve tired various diets and exercise, and he continues to gain weight,” said Dr. Armstrong, who is a professor of pediatrics at Duke University. The boy developed diabetes and became so large that his family took him out of school because he was a target for bullying. He now weighs 400 pounds, and the clinic is petitioning Medicaid to pay for bariatric surgery.

“If he had cancer and needed chemotherapy, no one would tolerate this,” Dr. Armstrong said. “People view obesity as the parent’s fault, the child’s fault,” and believe that the state shouldn’t be paying. So the clinic is faced with “these really sick children, and there’s a safe and effective treatment right down the street and I can’t get them there.”

For the first time, the American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a policy statement on bariatric surgery for adolescents. Dr. Armstrong was the lead author on the policy statement and a co-author on the accompanying technical report, which summarized all the available evidence about a form of surgery that is increasingly accepted as an effective therapy for adults, but is often regarded negatively for younger patients — including by their pediatricians.

“Twelve million kids in the U.S. have obesity and over four million have severe obesity,” she said, calling it “an epidemic within an epidemic.” We have not made the kind of categorical changes in our environment that might address this epidemic, she said, though we must keep trying. “These children aren’t just more overweight than their peers,” she said. “They’re sick.” Some of them are on insulin, others take one or more medication to control their blood pressure.

Most important, bariatric surgery seems to work well for adolescents with severe obesity. Over the past decade, Dr. Armstrong said, there has been a fair amount of research on bariatric surgery in people under 18. “It’s safe,” Dr. Armstrong said. “It’s effective — at least as effective as in adults.”

Like most pediatricians who have become involved with obesity and weight management, Dr. Armstrong did not go into this looking for surgical remedies. Her own research centers on getting children outdoors into nature. “I believe active physical exercise outdoors improves life, reduces stress,” she said. “This is what I love, it has nothing to do with surgery — but in my practice a lot of the kids can’t even get there because they’ve got such severe obesity.”

Children who have bariatric surgery, she said, reverse their medical complications very quickly. More than 80 percent of those who have been given diagnoses of Type 2 diabetes resolve after the procedure. Similarly, almost 90 percent of the cases of sleep apnea get better following surgery. The procedure also reverses high blood pressure, although not quite as effectively.

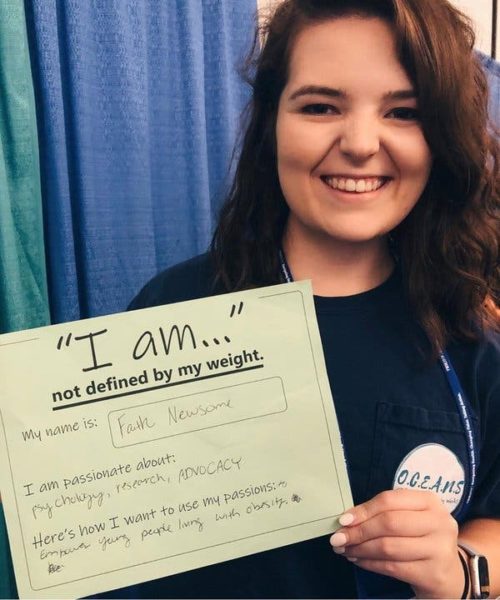

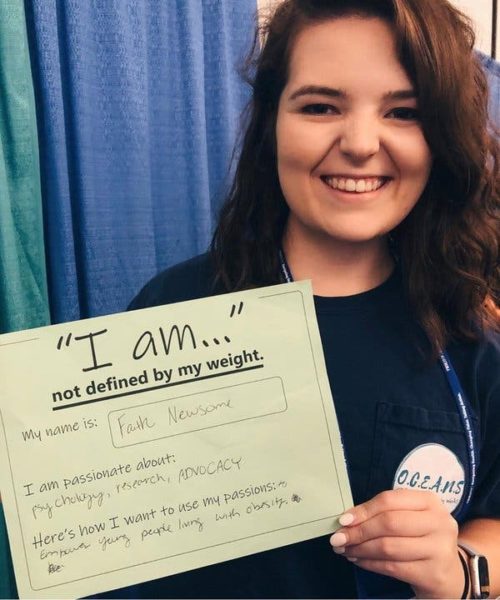

One of Dr. Armstrong’s patients, Faith Newsome, now a senior at UNC Chapel Hill, where she is studying psychology, said, “I personally have never known a time in my life when I haven’t carried excess weight.” She would bring her own sugar-free candy to sleepovers. She has stories of being bullied, of humiliation at field day.

Certainly this was no quick fix. She went through a yearlong process of trying supervised weight loss, driving an hour and 15 minutes every month to meet with a physician, a dietitian and a mental health specialist. “I would have to take that entire day off school, my mom off work,” she said. “We had to do this once a month for a year before we could be referred to a bariatric center.”

After she had the surgery, at 16, her hypertension and prediabetes got better. She was honest with her college roommates, not wanting them to see the small meals she needed after surgery and think she had an eating disorder. She had to navigate other problematic college food situations, she said, with cookie deliveries and late-night pizza expeditions. But from a weight of around 270 pounds (she is 5 foot 8), she has now stabilized around 190. “I’m still technically from a B.M.I. category considered overweight,” she said. “I’m comfortable and I’m happy with my body.” She is serious about fitness and works out four or five times a week.

Perhaps the most sensitive question the policy statement examines is: How young is too young? Most of the studies involve older adolescents, though some international research looked at 12- or even 10-year-old patients. There is no lower age limit in the policy statement because the researchers could not find evidence drawing a firm line to mark a lower age boundary; the decision should rest with a whole team, including the child and the family, the pediatrician and the surgeon.

There are major disparities in access to bariatric surgery. “Childhood obesity disproportionately affects children of color and those in low-income populations,” Dr. Armstrong said. “Those getting access to surgery are almost exclusively middle- and upper-class white adolescents.” The biggest barrier is lack of insurance coverage; many private payers will not cover the surgery for those under 18, and almost no public payers will.

Often, childhood obesity is seen as the parents’ fault, and some worry that bariatric surgery is being offered as a quick fix. Dr. Armstrong noted that in many cases, the parents themselves “have struggled with their weight most of their lives and want nothing more than to have their kids not go through this.” She added, “Most of them have tried everything they were capable of doing” to help their children lose weight.

The impulse to keep trying with diet, nutrition and behavioral modifications runs deep in pediatrics, but the evidence suggests that if an adolescent needs bariatric surgery, it’s better not to wait too long, Dr. Armstrong said. “Watchful waiting for extended periods of time can actually lead to less effective surgery and surgery with more complications.”

Weight loss surgery generally reduces B.M.I. by about 10, so if the patient is a 16-year-old with a B.M.I. of 45 (anything over 35 generally meets the criteria for severe obesity), the B.M.I. going into adulthood after surgery is likely to be around 35 — still obese, but much less severe. On the other hand, if the same child waits until the age of 19, when the B.M.I. may have gone up to 55 — you can do the math.

To be eligible for the surgery, adolescents undergo a psychological assessment, which includes a careful look at their maturity level and their ability to understand the risks and benefits. If there is a mental health condition, such as depression, it needs to be assessed and treated.

Ms. Newsome decided she wanted to go into obesity-related work as a profession. She started an organization called OCEANS, a support and advocacy group for people ages 12 to 21 living with obesity. “When I was growing up I felt I was the only person experiencing this,” she said. “We really need to start connecting teens with each other.”

“At the end of the day, we are left saying obesity is a chronic disease,” Dr. Armstrong said. “Everybody has something they have to cope with — for this child, this is going to be their mountain to climb in life — rather than looking for a quick fix, we need good partners to help us climb.”