When you shop through retailer links on our site, we may earn affiliate commissions. 100% of the fees we collect are used to support our nonprofit mission. Learn more.

It was a brisk, windy morning on March 21, 2018, when Linda Chapman entered the glassy law offices in Buffalo, N.Y., near the headquarters of her employer, Fisher-Price, to give her deposition. As the product designer who’d invented the company’s popular Rock ’n Play Sleeper, she was there with other employees to testify in a lawsuit alleging that the sleeper, meant for babies, could be a death trap.

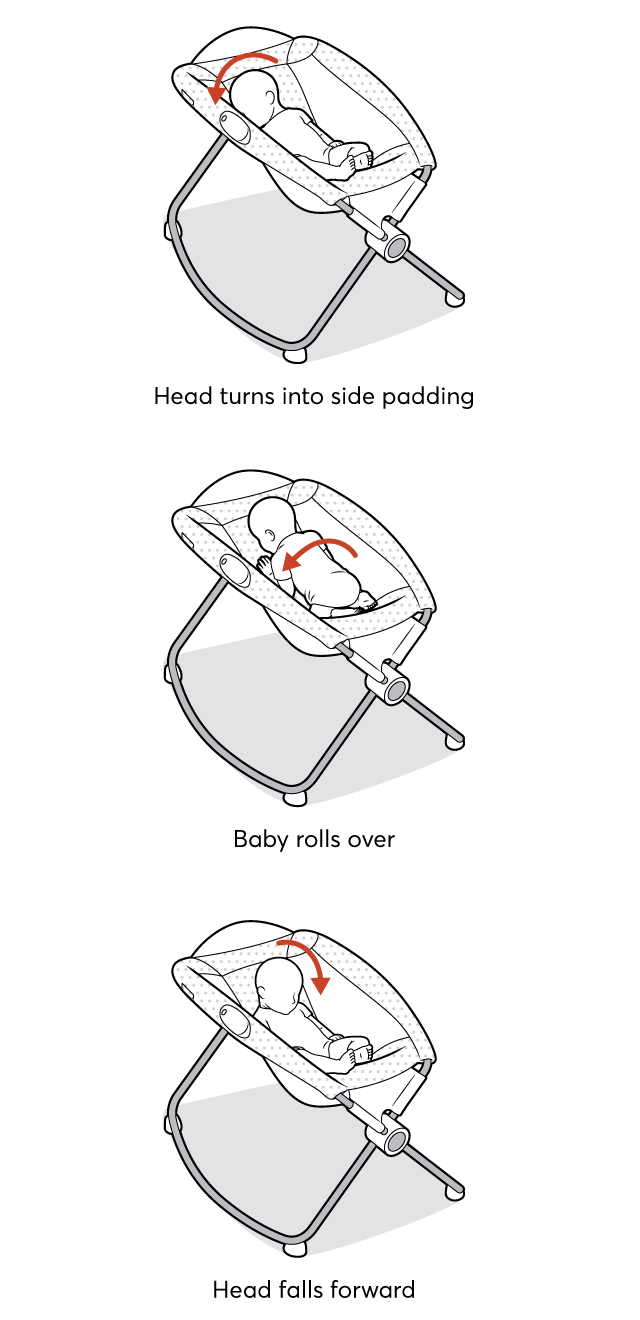

Courtney and David Goodrich of Atlanta had brought the case after their 7-week-old son Asher had nearly died in the sleeper in July 2014. He was napping when Jan Hinson, Asher’s grandmother, noticed his head oddly flopped forward and to the side. When Hinson got closer, she saw that Asher wasn’t breathing and that his face was blue. “When I grabbed him, I smacked his diaper, which made him start gasping for air,” Hinson says.

After a short hospital stay, the baby recovered. But the family grew outraged when they later learned that the likely culprit in Asher’s near-death was the sleeper itself. Infant heads are large and heavy in proportion to their body size and neck strength, and the sleeper’s 30-degree incline allowed Asher’s head to slump forward, blocking his trachea.

Hinson, who is both a practicing lawyer and a former respiratory therapist, called Fisher-Price to alert the company to the problem. But company representatives said they stood by the safety of their product and had no plans to investigate, she says. So the Goodriches sued. “We could not stand the thought of another baby suffocating in the Rock ’n Play Sleeper,” says Hinson, who did not represent the family in the lawsuit.

Asher’s life-threatening episode wasn’t the only serious incident reported to Fisher-Price. During the March 21, 2018, deposition, a company employee revealed that since the Rock ’n Play Sleeper had been introduced nearly 10 years earlier, the company was aware of 14 infant deaths tied to the sleeper.

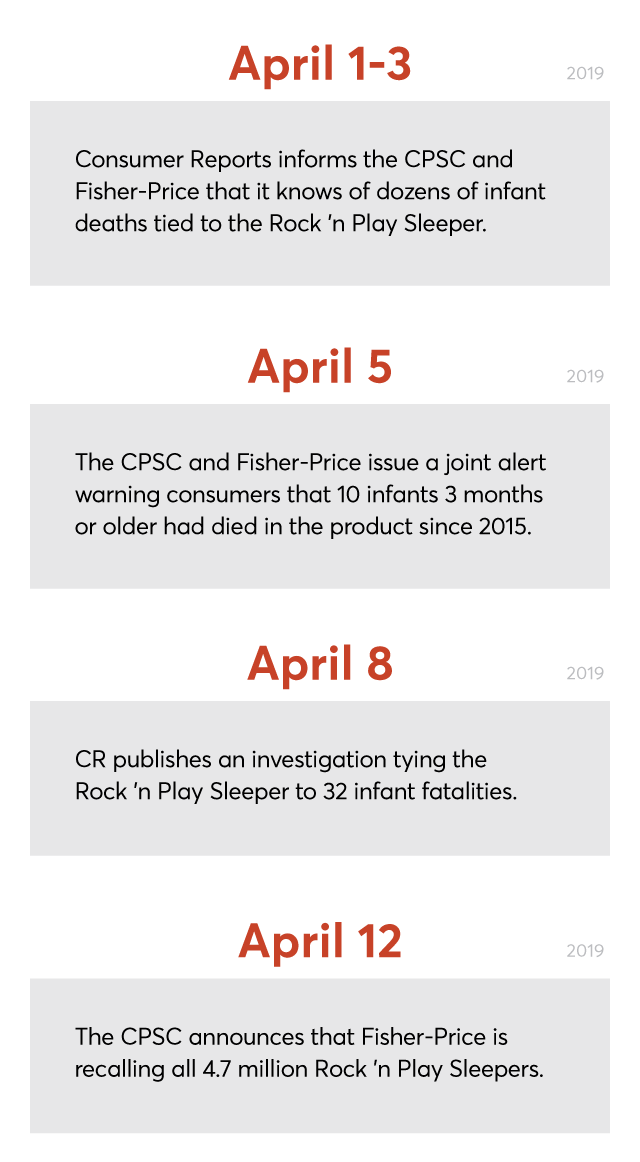

In fact, the very same morning that Chapman was being deposed in Buffalo, Veronica Goans—a young mother some 700 miles away in Knoxville, Tenn.—woke to find her 7-week-old daughter Lilly lying unresponsive in her Rock ’n Play Sleeper. Goans had placed the sleeper near her bed so that she could be close to her baby at night. It was only the second time she’d put Lilly in it, Goans says—“the worst mistake of my life.”

Though Fisher-Price didn’t know it at the time, that day the death count linked to the Rock ’n Play Sleeper rose by one more.

Also shown: Veronica and Trenton Goans. Photo: Courtesy of Veronica Goans

Fast forward one year, to April 12, 2019. After Consumer Reports obtained government data linking Fisher-Price’s sleepers to dozens of infant deaths, the company recalled all 4.7 million of its Rock ’n Play Sleepers. Two other manufacturers that made similar sleepers, Kids II and Dorel, soon recalled their products as well. Ultimately, the Rock ’n Play Sleeper and other infant inclined sleepers were linked to at least 73 deaths and more than 1,000 incidents, including serious injuries.

By early December 2019, major retailers such as Amazon, eBay, Buy Buy Baby, and Walmart vowed to pull all infant inclined sleepers from sale, even those that hadn’t been recalled. And before the end of the year, the U.S. House of Representatives voted to ban the sale of infant inclined sleepers. That bill is now in the Senate.

The story of how this unsafe infant sleep product was introduced, quickly became a must-have item among new parents, and stayed on the market for nearly a decade shines a bright light on critical failures in the U.S. product safety system. It is a cautionary tale about how the government agency that is supposed to protect consumers from dangerous products is forced to keep important information about injuries and deaths shrouded in secrecy because of pressure from manufacturers. It also illustrates just how much leeway manufacturers have to bring products to market without potentially lifesaving checks and balances. And finally, it outlines the marketplace changes that are needed to ensure that dangerous products don’t spend years sitting on retail shelves and in American homes.

When Linda Chapman’s son was a baby in the late 1990s struggling with reflux, her pediatrician suggested that elevating his head would ease his discomfort and help him sleep through the night. But when the Fisher-Price employee looked for a sleeper that would prop him up, she couldn’t find one, Chapman said in her deposition in Buffalo. The memory of that difficult period stayed with her, and in 2008 she decided to design a product for parents as exhausted as she used to be.

More on Safe Sleep

CR’s Complete Infant Inclined Sleeper Coverage

Fisher-Price Rock ‘n Play Sleeper Should Be Recalled, Consumer Reports Says

More Infant Sleep Products Linked to Deaths, a Consumer Reports Investigation Finds

Though Chapman had been a designer at Fisher-Price since 1990, she worked primarily in the area of imaginative play, creating toys such as the Pinwheel Choo-Choo, a small plastic train with a multicolored pinwheel, and a life-sized outdoor Barbie playhouse meant for pretend tea parties. The product that came to be called the Rock ’n Play Sleeper was the first sleeper she’d ever designed.

What Chapman didn’t know was that her pediatrician’s advice was medically wrong. Since 1994 the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guidelines have recommended that babies sleep alone on their backs on a firm, flat surface that is free from soft bedding and restraints. The Rock ’n Play Sleeper is not flat, its sidewalls and head support are made of soft bedding, and it has a restraint harness. Further, pediatric gastroenterologists have known since before the 1990s that placing babies on an incline does not ease their reflux, says Jenifer Lightdale, M.D., past chair of the AAP’s task force on Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition. Sleeping on an incline may even worsen the problem, she says.

Any advice to the contrary, no matter how popular the belief, was not based on scientific evidence. During the design process, however, Chapman never confirmed that her proposed product met accepted medical advice. When asked during the deposition, “Do you ever research any of the medical or regulatory conditions of the product?” she answered, “I do not. There’s a team of people at Fisher-Price, and that’s their responsibility.”

But members of that safety team didn’t research the medical premise of the Rock ’n Play Sleeper, either. “That was not part of my charge at that time,” said Michael Steinwachs, the project’s product integrity engineer on the hazard analysis team, who was deposed in the Goodrich lawsuit a day after Chapman. That was the responsibility of Kitty Pilarz, he said, who was then a director of product safety for Fisher-Price’s parent company, Mattel.

Safe and Sound

Help support our work to ensure you have the safest products possible.

Donate Now

Turns out, though, that Pilarz also didn’t research the safety of infant inclined sleep, according to her testimony in the Goodrich lawsuit and an earlier one involving a baby girl from Hidalgo County, Texas, found dead in a Rock ’n Play Sleeper in 2013. Pilarz said that she read no medical literature about inclined sleep, that she never contacted the AAP or talked to a pediatrician at any other medical organization about it, and that nobody at Fisher-Price conducted independent testing to verify that the sleeper’s 30-degree angle was safe for babies.

But that’s not the story Fisher-Price told on its website when it was marketing the sleeper. On a page that has since been removed, called “A Design Story,” Chapman describes how the sleeper was born, going so far as to include a picture of her baby son on the page:

“When we approached the Fisher-Price Safety Committee with this idea, they had . . . concerns. But they also recognized the need. Our design and engineering team put a lot of thought into the best way to do this. We had to find just the right angle for elevation, and just the right range for rocking motion. Choosing fabrics was key, too—adding mesh on the sides for air flow and comfort.”

Illustration: Chris Philpot

But Steinwachs’ testimony indicated that when it came to determining the sleeper’s angle, the various teams did little more than hazard a best guess: “The only standards or best practices that we know [concerning inclined products] are related to infant car seats. And infant car seats have the best practice to never have them angled with a seat back angle greater than 45 degrees. So we chose 30, which is well below 45 degrees, and the 30 degrees was determined to be a conservative safe angle.” (Car seats are designed and extensively tested to ensure a child’s safety while traveling in a vehicle, not for extended sleep.)

The only medical advice the team did seek out was that of a physician named Gary Deegear, of San Antonio, Texas, who had consulted for Fisher-Price for 20 years, according to Pilarz. But Deegear was a questionable choice. He was a family physician, not a pediatrician or a sleep specialist. And emails show that he offered reassurance that a 30-degree angle “was just fine”—advice that directly contradicted established infant sleep guidelines. And in the years following his work on the Rock ’n Play Sleeper, the Texas Medical Board issued a cease-and-desist order forbidding him from treating patients after it learned that he had been practicing, sometimes under the influence of drugs or alcohol, even though his license had lapsed.

Deegear did not respond to multiple requests for comment. Fisher-Price told CR that “safety is our highest priority” but could not comment in more detail because of ongoing litigation.

With suspect medical advice as its basis, Fisher-Price introduced the Rock ’n Play Sleeper in October 2009, marketing it for naps and nighttime sleep “from birth until child becomes active and may be able to climb out of the product.” It wasn’t long before parents started raving about it. Many moms and dads, desperate for a respite from sleepless nights, claimed it was a “lifesaver,” the only place their baby would sleep.

But behind the scenes, impending regulatory changes threatened the new product’s survival, almost from its launch. Fisher-Price had brought the sleeper to market adhering to a safety standard for bassinets—small beds on legs that often rock, meant for babies up to about 5 months old—developed by ASTM International, which is an organization that gathers manufacturers, government officials, medical experts, consumers, and others to create voluntary standards for products. (Consumer Reports is a member of ASTM.)

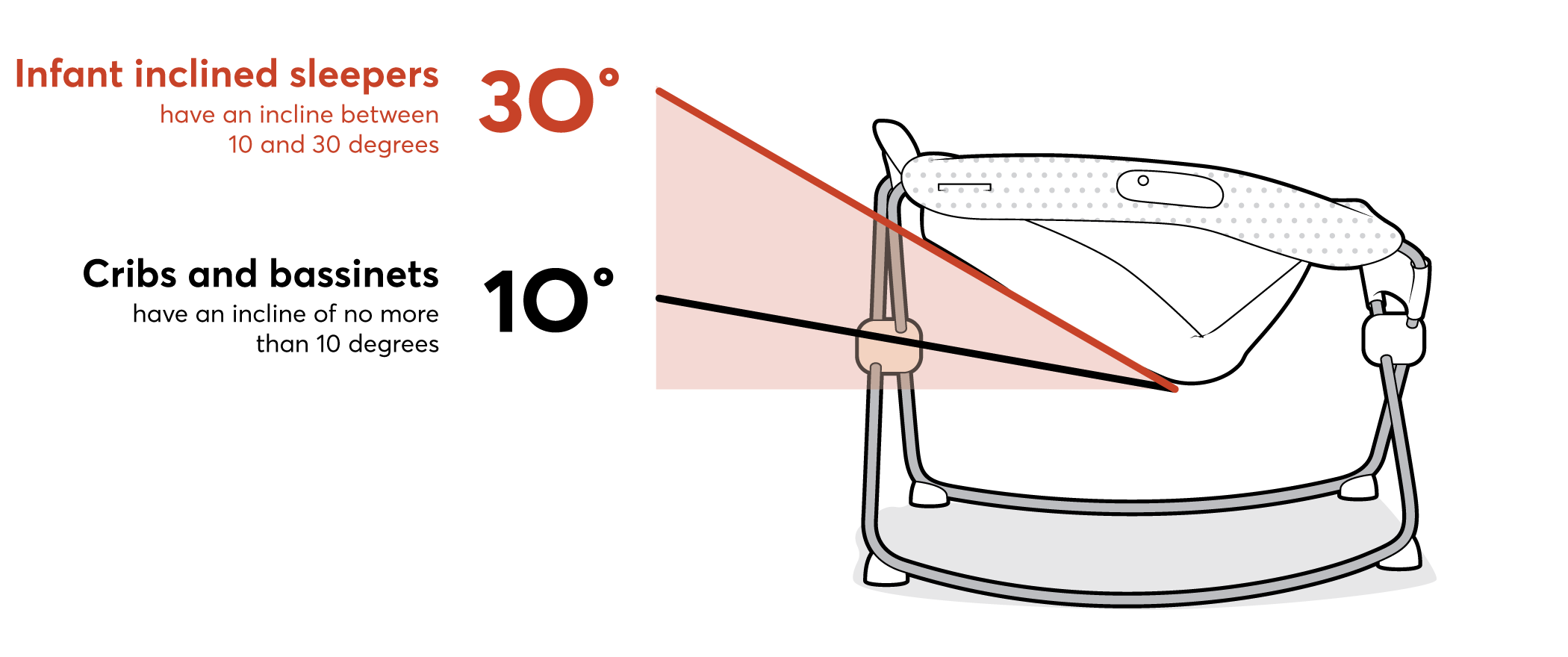

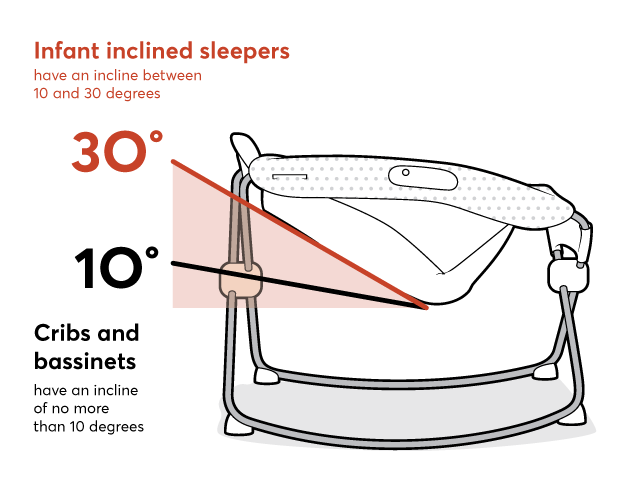

The bassinet standard at the time didn’t specify an angle for the product. But a recently passed law—the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act—had required that safety standards for many children’s products be revised and made mandatory. And so in April 2010, just six months after the Rock ’n Play Sleeper hit store shelves, new standards for bassinets were proposed by the Consumer Product Safety Commission, the federal agency tasked with ensuring that consumers are protected from dangerous products. The agency was specific in its proposal, requiring that bassinets be firm and flat. The final standard would specify a maximum incline of 10 degrees.

The Rock ’n Play Sleeper, with its 30-degree incline, would no longer pass as a bassinet. But rather than redesign its hit product, Fisher-Price asked the CPSC for an exemption. In a July 12, 2010, letter to the agency, Pilarz requested that a new product category be created for sleepers, such as the Rock ’n Play Sleeper, that have restraints and an incline up to 30 degrees.

Pilarz wrote that if inclined sleepers could not be sold, it “could even increase children’s risk of injuries as parents reach for substitutes.”

The CPSC agreed, paving the way for Fisher-Price to propose a new product category to ASTM called infant inclined sleep products. The chairman of the ASTM subcommittee charged with creating the standard was none other than Michael Steinwachs, the Fisher-Price product engineer who helped develop the Rock ’n Play Sleeper.

Illustrations: Chris Philpot

Safety advocates were alarmed, having had doubts about the product’s safety since its launch. “Our concern was that babies could slump or fall into an unsafe position, and we knew that adding a restraint during sleep could become a hazard itself,” says Nancy Cowles, executive director of Kids in Danger, a nonprofit dedicated to preventing childhood injury from products. “By creating a standard, it would give new parents a false sense of security about a product that was unsafe,” Cowles says. “It should never have been on the market.”

Health and regulatory agencies in other countries also pushed back. In January 2011, Australian regulators said the Rock ’n Play Sleeper could not be sold because it did not meet widely accepted best practices for infant sleep, and that a baby’s head could easily fall forward in a way that obstructs the airway. Soon after, the Royal College of Midwives in the United Kingdom told Fisher-Price that it would not endorse the product as a sleeper because it was only suitable for short periods of supervised wakefulness. Around the same time in Canada, public health authorities intervened and only allowed the product to be sold as a Rock ’n Play Soothing Seat rather than a sleeper. To accommodate the decision, Fisher-Price changed the warnings in the product’s instruction manual sold in Canada, stating “never leave child unattended” while in the product.

None of this deterred Fisher-Price, even though one mother, Sara Thompson, of Nazareth, Pa., wrote to the CPSC in December 2012 telling the agency that her son had died in the Rock ’n Play Sleeper in September 2011. “My 15 week old son died in the last Rock N Sleeper we had . . . and ruled SIDS,” she wrote. The CPSC passed the information to Fisher-Price’s risk-management team, which documented the incident as an “injury flag,” according to internal company files obtained through the Goodrich lawsuit.

Fisher-Price also stood its ground after some U.S. pediatricians began voicing concerns. Roy Benaroch, M.D., a pediatrician in Georgia and an adjunct associate professor at Emory University in Atlanta, called and wrote to Fisher-Price in February 2013 to warn that the product was unsafe for infant sleep. The company responded by email, writing that “the Rock ’n Play Sleeper complies with all applicable standards.” (It’s hard to know which standards they referred to, though, because the product didn’t qualify as a bassinet and the new category for infant inclined sleep products wouldn’t come into effect until 2015, nearly two years later.)

After Benaroch posted an entry about his interactions with Fisher-Price in his blog, several lawyers asked him to serve as an expert witness in lawsuits that were quietly being filed involving deaths and injuries tied to the Rock ’n Play Sleeper.

Yet for the most part, the public remained blissfully unaware of the dangers of the Rock ’n Play Sleeper, which was becoming ubiquitous across the country in new parents’ homes and in day-care centers. The product ranked as a No. 1 best seller on Amazon and was given a “Moms Love-It” award by WhatToExpect.com and Babies “R” Us. The product’s success inspired other companies to create similar versions, spawning a spate of look-alikes.

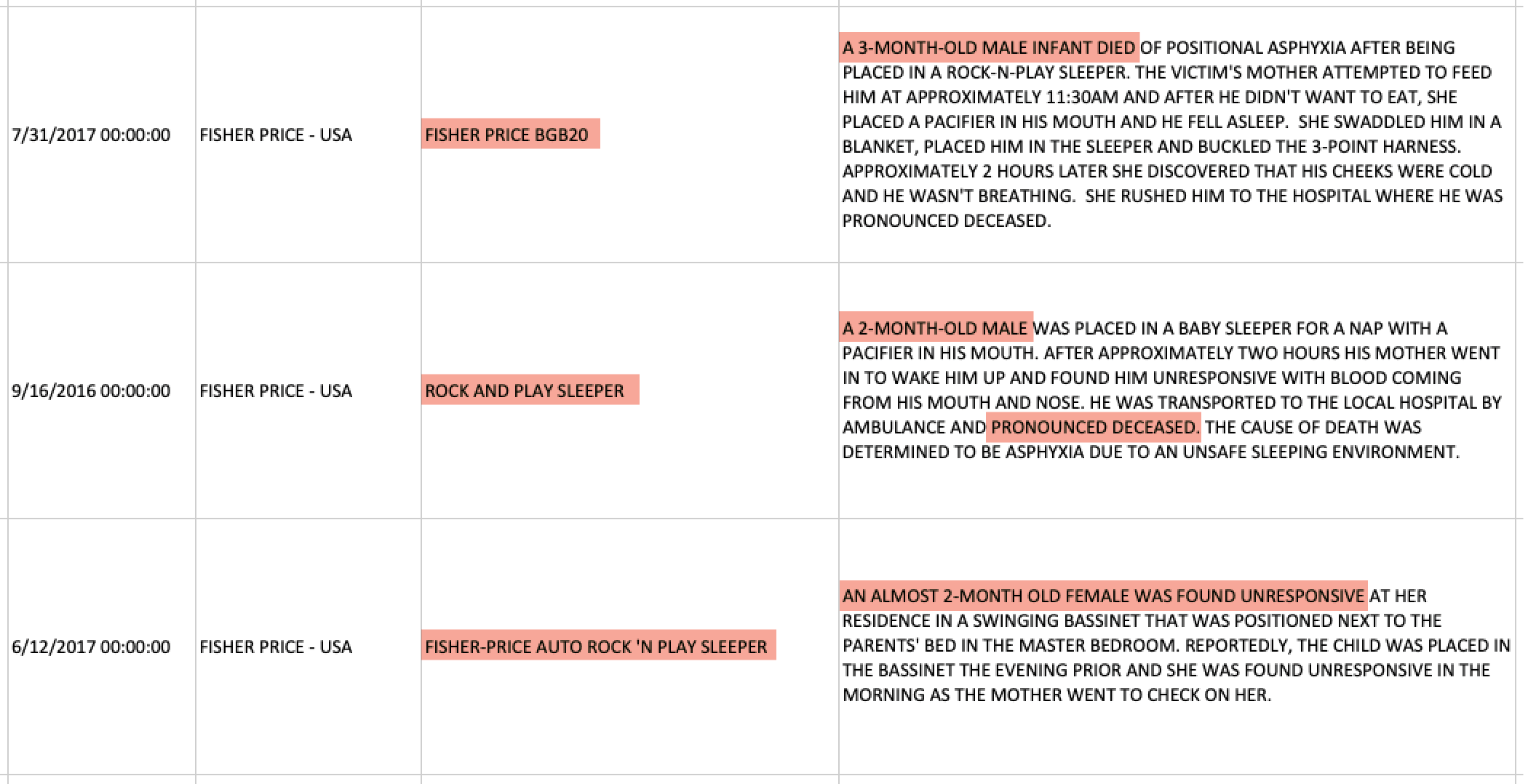

And as the months and years passed, the number of deaths related to the sleepers increased. They were largely hidden from the public but reported privately to the CPSC by manufacturers, hospitals, and consumers. The incidents often followed a similar, chilling pattern: The 2-month-old baby girl in Hidalgo County, Texas, found on her back in a Rock ’n Play Sleeper with her chin on her shoulder, cutting off her airway; a 2-month-old boy in Jacksonville, Fla., discovered by his mother with blood coming out of his nose and mouth after a nap in his sleeper; and a 3-month-old boy in Leesville, La., found with cheeks cold, pacifier in his mouth, not breathing.

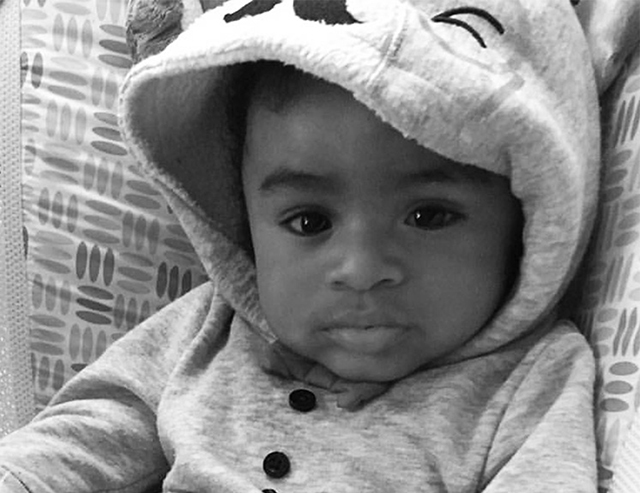

Photo: Courtesy of the Overtons

Some babies, like 5-month-old Ezra Overton of Alexandria, Va., were found dead on their bellies, after having rolled over. He’d been put to sleep on his back one night shortly before Christmas 2017 and found in the middle of the night with his face pressed against the sleeper’s padding. “He was blue, and his body was, it was hard, and he didn’t feel real,” says Ezra’s dad, Keenan Overton. Ezra was pronounced dead at the hospital, with asphyxia the immediate cause of death.

Yet as the death toll rose, Fisher-Price did not pull its product from the market or make design changes. During her deposition in the Hidalgo County lawsuit, Pilarz was asked to confirm that Fisher-Price had not changed how it marketed the Rock ’n Play Sleeper despite evidence of the deaths. Her reply: “Correct.”

“Is there a particular number [of] children that have to die before that’s going to be looked into?” the plaintiff’s lawyer then asked. Pilarz was silent.

The CPSC, too, stayed largely mute on the growing number of deaths, despite the lawsuits. One reason is a controversial law that applies uniquely to the agency. It requires the CPSC to seek permission from manufacturers before publicly releasing information about the company or their products, even when it is warning about injuries or deaths. The law, known as Section 6(b) of the Consumer Product Safety Act, also allows companies to negotiate the language the CPSC uses in press releases in the event of a safety alert or product recall.

Proponents of 6(b) say that by giving companies a chance to review safety concerns first, the law prevents the CPSC from unfairly damaging a company’s reputation.

But critics of the law—who include safety advocates and even some current and past CPSC commissioners—say that Section 6(b) protects manufacturers at the expense of consumer safety.

“We need the anti-consumer safety and anti-transparency requirements of Section 6(b) … to be eliminated,” Elliot Kaye, a CPSC commissioner and former chairman, said in early April 2019 at a subcommittee hearing of the House Energy and Commerce Committee. “People die because of Section 6(b). It is that simple.”

The CPSC is limited not just by 6(b): It also does not have unilateral recall authority, even for products with clear safety hazards. Instead, it must get the company’s buy-in, or take the company to court—an expensive, time-consuming step it rarely takes.

Eventually, on May 31, 2018, nine years after the Rock ’n Play Sleeper’s launch, the CPSC did issue a mild warning in the form of an alert posted on its website titled “Caregivers Urged to Use Restraints with Inclined Sleep Products.” It vaguely warned consumers to “be aware of the hazards when infants are not restrained in inclined sleep products,” and to “always use restraints and stop using these products as soon as an infant can roll over.”

Only in the alert’s fourth paragraph was the possibility of death mentioned: “CPSC is aware of infant deaths associated with inclined sleep products. Babies have died after rolling over in these sleep products.”

Still, the announcement did not list products by name and appeared to trigger no public backlash or drop in sales, possibly because many parents had no idea what an “infant inclined sleep product” was, says Rachel Weintraub, general counsel for the Consumer Federation of America. As with Kleenex and tissues, the product was popularly known simply as the “Rock ’n Play Sleeper,” so even parents who owned one may not have known they were putting their baby in an “infant inclined sleep product.”

By not naming specific products, the CPSC gave parents little way of knowing whether they had a hazard in their homes. Further, the alert failed to acknowledge that not all babies had died as a result of roll-over, but also on their backs and while restrained. Finally, the CPSC failed to warn parents that using restraints and putting babies to sleep on an incline went against the AAP’s safe sleep guidelines.

“When the government’s hands are tied and they are thwarted from communicating the full story, it very much limits the utility of that information,” Weintraub says.

One day last winter CR was reviewing data requested from the CPSC. It included information on product failures, injuries, and deaths that manufacturers, healthcare providers, and consumers had provided to the agency—something CR analyzes regularly. But this time, there was something unusual: The manufacturer and product names were not redacted, per Section 6(b) requirements.

The government agency had made a mistake. And there in plain view were details of at least 19 infant fatalities attributed to the Fisher-Price Rock ’n Play Sleeper and similar products made by Kids II (and likely up to 29 deaths linked to the Rock ’n Play Sleeper alone, based on incomplete reports). For the first time, the vast scope of deaths, as well as the brands that had caused them, was transparent.

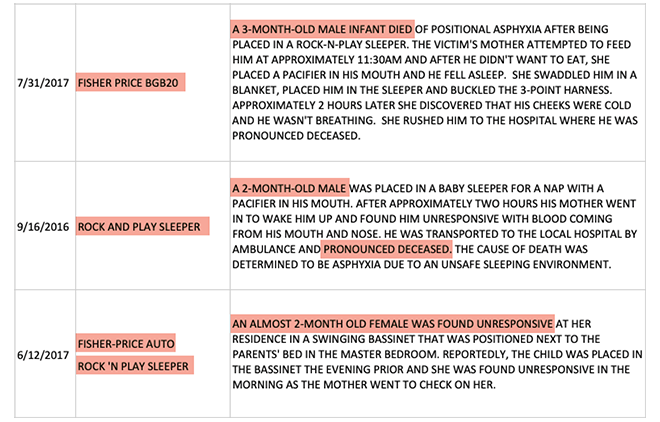

Though names and street addresses of families were not shown in the government files, CR used lawsuits, police reports, and social media postings to find and contact parents who had been affected, and to unearth additional deaths not in the data. CR also spoke with pediatric sleep specialists, children’s product designers, and other experts to better understand the risks posed by infant inclined sleepers. And on April 1, 2019, CR contacted the CPSC and, soon after, Fisher-Price for comments.

Source: CPSC

The CPSC’s lawyers sent letters to CR demanding we destroy the data and not publish anything based on it. Fisher-Price delayed comment.

On April 5, 2019, Fisher-Price and the CPSC issued a joint public announcement. It was another alert, this one warning that 10 infants 3 months or older had died in the Rock ’n Play Sleeper since 2015 after they “rolled from their back to their stomach or side, while unrestrained.”

After the alert’s release, CR reiterated to Fisher-Price that in the course of reporting it had learned of at least 29 infant deaths tied to the Rock ’n Play Sleeper, which was 19 deaths more than the manufacturer and the CPSC had publicly acknowledged.

That weekend, a Fisher-Price spokesperson confirmed to CR that the company knew of “approximately 32 fatalities since the 2009 product introduction.” The response also noted that Fisher-Price did “not believe any deaths have been caused by the product.”

On Monday, April 8, 2019, CR published its investigation tying the Rock ’n Play Sleeper to dozens of deaths and calling for its recall. The response was swift, with the findings airing nationally on evening news programs and published online and in newspapers across the country.

The next day, the American Academy of Pediatrics also urged the CPSC to recall the sleeper. Citing CR’s investigation, the AAP cautioned parents to stop using “inclined sleep products like the Rock ’n Play, or any other products for sleep that require restraining a baby,” and noted that the “warning issued by the CPSC and Fisher-Price on April 5 did not go far enough to ensure safety and protect infants.”

Later that same week, CR published a follow-up article on deaths linked to the Kids II inclined sleepers. And on Friday April 12, 2019, the CPSC announced that Fisher-Price was recalling all 4.7 million Rock ’n Play Sleepers. By the end of the month, Kids II recalled all of its nearly 700,000 infant inclined sleepers. (See CR’s full investigation into infant inclined sleepers.)

The news of the recalls prompted more families to come forward. On SaferProducts.gov—the CPSC website where consumers can publicly report problems with products—additional fatalities began flooding in.

In one such report, submitted just days after the Rock ’n Play Sleeper was recalled, a mother wrote: “On April 21, 2016, my week-old son was laying buckled in on the Rock ’n Play Sleeper while I was preparing the needs for his feeding. When I went to pick him up to feed him his face was turned into the side of the rocker and was not breathing. 911 was contacted, CPR was provided, and he was rushed to the hospital. After being treated for an hour and a half he was pronounced dead. … Why did it take so many deaths and so many years to say anything about the incidents?”

As it would happen, just three days after that 2016 death, Michael Steinwachs—the Fisher-Price product safety engineer—received an award from ASTM for his “leadership and technical contributions resulting in the development of [the standard] for Infant Inclined Sleep Products.”

As controversy around its product unfolded, Fisher-Price continued to maintain that its Rock ’n Play Sleeper was safe when used as directed. The company even seemed to suggest that parents were responsible for the injuries and fatalities. For example, the company’s April 5, 2019, alert stated that “the reported deaths show that some consumers are still using the product when infants are capable of rolling and without using the three point harness restraint.”

It would later become clear that the restraints did not prevent deaths, yet this misleading narrative continued even after the recall. In a message on its website describing the recall, Fisher-Price general manager Chuck Scothon said, “While we continue to stand by the safety of all of our products, given the reported incidents in which the product was used contrary to safety warnings and instructions, we’ve decided in partnership with the Consumer Product Safety Commission … that this voluntary recall is the best course of action.”

Photo: Courtesy of Sara Thompson

That idea—that parents were to blame for their own babies’ deaths—still haunts Thompson, the mother who contacted the CPSC in December 2012. Her son Alex had never rolled over in the product, she says. In fact, the morning he died, Thompson had placed him on his back and found him less than 15 minutes later in the same position—not breathing. She’d only learned about the sleeper’s connection to her son’s death through CR’s investigation, nearly eight years after Alex died.

In addition to her grief, Thompson has been burdened by attacks on social media from consumers who blame her for her son’s death. “So many people believe what Fisher-Price said, that it’s all deaths from babies rolling over. At what point is Fisher-Price forced to take ownership for publicly blaming all the parents of the babies who died?”

In the months after the recalls, CR found that sellers on Craigslist and Facebook Marketplace continued to list sale posts for secondhand recalled inclined sleepers made by Fisher-Price and Kids II. Though it’s illegal to sell recalled products, the websites did little to prevent these transactions. While some sellers might not have been aware of the recalls, others, using the hashtag #BlackMarket, said that although the Rock ’n Play Sleeper had been recalled, it was a “lifesaver” for them and that as long as it was used with the restraints, it would likely be fine.

A separate investigation by two consumer groups—Kids in Danger and U.S. PIRG—also found that some day-care centers were still using the inclined sleepers after the recall. The groups surveyed nearly 400 day cares in Georgia, Texas, and Wisconsin, and found 1 in 10 still used the sleepers. One of the report’s co-authors initiated the investigation after his wife saw a Rock ’n Play Sleeper in their son’s day care. The provider told him she thought there was only a warning about the sleeper, and it was fine to use as long as the child was restrained.

The cost of that continued use was more lives lost. One report posted this fall on SaferProducts.gov documented that a 1-month-old girl died in the Rock ’n Play Sleeper on Sept. 15, 2019, five months after the product had been recalled.

“These incidents underscore how hard it is to get a recalled product out of homes‚ even one whose dangers seem well-publicized, once it’s already out there on the market,” says safety advocate Cowles, of KID.

While the Fisher-Price and Kids II rocking inclined sleepers were recalled, other manufacturers—including Baby Delight, Evenflo, and Hiccapop—continued to sell similar inclined sleepers. And the industry continued to support them.

In May 2019, the ASTM subcommittee on infant inclined sleepers gathered without a chairman. Fisher-Price’s Joel Taft, a senior product safety manager who had succeeded his recently retired colleague Steinwachs as chairman of the subcommittee, stepped down shortly before the meeting. Nevertheless, the group decided that more research was needed before eliminating the product category.

Consumer representatives on the committee were aghast. Thompson—whose son Alex had died in a Rock ’n Play Sleeper and who had recently joined the committee as a consumer representative—broke into tears. “How could they still need more data or more research in order to get rid of these products after all of these deaths?” she asked.

But through the summer and into the fall, pressure for stronger action against inclined sleepers steadily built as, in rapid succession, more medical experts and elected officials spoke out, and more deaths and recalls were announced.

Ben Hoffman, M.D., chairman of the American Academy of Pediatrics’ Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention, implored the CPSC at a hearing to “eliminate this product category altogether so these deadly products are no longer available.” He stressed that the “CPSC sends parents a dangerous message by allowing other inclined sleep products to remain on the market.” Rep. Tony Cárdenas, D-Calif., and Sen. Richard Blumenthal, D-Conn., introduced the Safe Sleep for Babies Act to ban the manufacture, import, and sale of infant inclined sleep products.

In June 2019, the CPSC confirmed at least 50 deaths linked to rockerlike inclined sleepers, and an additional six deaths tied to stationary inclined sleepers, such as the Nap Nanny, which had been fully recalled in 2013. Fisher-Price also recalled about 71,000 inclined-sleeper accessories sold with one of its portable cribs. And another manufacturer, Dorel, recalled its rocking inclined sleepers, too, despite no associated deaths or injuries.

In mid-October a newly active CPSC—now under the leadership of Bob Adler, a Democrat who had recently replaced Republican acting chairman Ann Marie Buerkle, who left her role amidst criticism of her handling of several product safety issues—announced two pieces of news that signaled the demise of infant inclined sleepers.

First, the CPSC revealed that it knew of at least 73 deaths and a total of 1,108 incidents involving infant inclined sleepers, going back as far as January 2005. Those incidents involved other issues, too, including respiratory problems caused by mold, babies falling out of the sleeper, and two problems linked to being restrained in the same position for long periods, a flat-head syndrome called plagiocephaly and a contortion of the neck muscles called torticollis.

Second, the agency announced the findings of a new study it had commissioned, led by Erin Mannen, Ph.D., an expert in biomechanics and a professor at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, on how babies moved and breathed while at an angle between 10 and 30 degrees. Her conclusion: “None of the inclined sleep products that were tested and evaluated as part of this study are safe for infant sleep.”

Among her findings: Placing babies in inclined sleepers makes it easier for babies to roll over because it puts them into a scrunched up position—similar to a fetal tuck—that allows them to roll over earlier than they would be able to manage on a flat surface. That explains, she says, why many parents said their babies had never previously rolled over yet were found dead, in some cases while restrained, face down on their stomach in the sleeper.

That scrunched up position, however, is the very thing that Fisher-Price’s medical consultant, Gary Deegear, thought would make the product safe, according to an August 2009 email made public in legal proceedings. In that email, Taft, then manager of product safety at the company, said Deegear offered reassurance that even if a smaller infant were to “become ‘scrunched-up’ in the seat, he did not see this as an issue and stated that babies spend their entire time in the womb in a scrunched-up position . . . He stated that unless there is some type of anatomical variation or physical predisposition, a scrunched up occupant should not be compromised in any way.”

Mannen found that other design factors posed additional risks, such as the potential lack of breathability of the product’s sidewalls. “There’s something more than just the incline that is potentially unsafe about these products,” Mannen says.

Further, she noted that several of the deaths occurred among infants who were ill, undercutting Fisher-Price’s contention that the sleeper was especially helpful to children with reflux or congestion.

“This is the kind of basic safety research that should have been done 10 years ago, before these inclined sleepers were brought to market,” pediatrician Benaroch said after the study’s release.

CR asked Fisher-Price if Chapman, Pilarz, Steinwachs, or Taft—who all helped develop the Rock ’n Play Sleeper—had any comment on the CPSC-commissioned study, and if the company’s experience with the product had changed the way it vets new products. In response, a Fisher-Price spokesperson said, “Safety is our highest priority and for almost 90 years, generations of parents and caregivers have trusted Fisher-Price to provide safe, high-quality products for children. We work hard to earn that trust every day. As a matter of policy, given ongoing litigation, we cannot comment further.” Fisher-Price also did not comment on any of the individual incidents CR asked about.

It was at an ASTM subcommittee meeting on Oct. 21, 2019, at the organization’s headquarters in West Conshohocken, Pa., that support for inclined sleepers finally seemed to falter.

Mannen, who joined by phone, described the results of her study in straightforward, clinical terms, and outlined the inherent dangers of infant inclined sleepers before the assembled crowd, which included consumer safety advocates and representatives from government and industry. Fisher-Price’s Pilarz and Taft sat in the back row, with Pilarz hunched over her laptop. Both sat just feet from parent-advocate Thompson. Neither Pilarz nor Taft spoke. Thompson, who had hardened herself since her first ASTM meeting, held her tears.

Source: CPSC

As is typical at these regulatory meetings, nothing official was decided on the spot. But the mood in the room was different, with a sense of resignation from product manufacturers about the fate of inclined sleepers.

By the end of October, all five CPSC commissioners, representing both political parties, had voted to ban infant inclined sleepers and move forward with mandatory safety requirements for all infant sleepers. The agency also issued a statement cautioning consumers not to use any brand of infant inclined sleep products. The warning cited the CPSC-commissioned biomechanics study and “a growing body of evidence showing that inclined sleepers with higher angles do not provide a safe sleep environment for infants.”

At that point, says Nancy Cowles, of the consumer group KID, it was clear that “this product category would not survive.”

While the regulatory steps are put into motion—a process that could take months or years—safety advocates, including those at CR, have pressed for quicker action on the products still available for sale, urging retailers to remove them from their shelves and websites. By Dec. 6, 2019, Amazon, Buy Buy Baby, eBay, and Walmart had all agreed.

Acting CPSC chairman Bob Adler says the agency continues to pressure companies that have not yet recalled their products. “Manufacturers that are continuing to produce, market, and sell inclined sleepers are acting in a way that’s contrary to all the evidence that’s coming in on the safety of these products,” he says.

Perhaps even more important is reaching caregivers who still have inclined sleepers in their homes and continue to use them. “I know there are a lot of families who really felt like these inclined sleepers helped them, and we know that sleep is hard,” says Hoffman of the American Academy of Pediatrics.

But he reiterates that infant inclined sleepers are “fundamentally hazardous. And any family that uses an inclined sleeper at this point is taking an absolutely unnecessary risk with their infant that could mean everything.”

Linda Chapman, Joel Taft, and Kitty Pilarz still work at Fisher-Price. In April 2019, the same month the Rock ’n Play Sleeper was recalled, Chapman was promoted to director of product design for Newcomers Play and Sleep. Pilarz remains on the ASTM subcommittee for infant sleepers in addition to several other juvenile products committees. A statement on Fisher-Price’s website from her says, “Parents have trusted us for more than 80 years to provide safe products for their children, but we know we must still earn their trust every day. So, right from the start of a design concept, we work to make sure our products are as safe as they can be.”

Sara Thompson, whose son Alex died in a Rock ’n Play Sleeper in September 2011, has visited members of Congress to support legislation banning infant inclined sleepers. She lives with her husband and three children, and is still a member of the ASTM committee on infant sleepers.

Jan Hinson, the lawyer whose grandson almost died in a Rock ’n Play Sleeper, is still representing the Overtons, whose baby died in a Rock ’n Play Sleeper in December 2017. Hinson regularly contacts sellers on Facebook Marketplace and Craigslist who post Rock ’n Play Sleepers, offering to purchase them herself for a promise that the owner takes down the listing and destroys the product.

Veronica Goans, whose daughter Lilly died in a Rock ’n Play Sleeper in March 2018, is considering a lawsuit against Fisher-Price. She lives with her 6-year-old son and is currently pregnant with a girl.

The Juvenile Products Manufacturers Association, an industry trade group, still certifies infant inclined sleepers and is not ready to give up on the category yet, saying, “We believe it creates more risk when we eliminate an entire product category without strong data to support that need …Today’s data is insufficient to draw concrete conclusions on risks related to inclined sleepers, and we encourage additional research on this topic.”

The Consumer Product Safety Commission was investigated by the Senate Commerce Committee Democratic staff, which found in December 2019 that a “series of high-profile failures to effectively recall dangerous products have called into question the ability of the [CPSC] to adequately protect American consumers from unsafe and defective products,” and showed “a pattern of inappropriate deference to industry.” When asked by CR why it took close to 10 years for the agency to recommend banning infant inclined sleepers, a spokesperson said, “CPSC continues our efforts to recall these products and to educate consumers on the hazards associated with these products.”

Consumer Reports continues to call on industry and the CPSC to protect consumers. And we are still connecting with parents whose babies died or were injured in infant inclined sleepers. If you have a story, please share it with us.