Kurbo Health, a mobile weight loss solution designed to tackle childhood obesity which was acquired for $3 million by WW (the rebranded Weight Watchers), has now relaunched as Kurbo by WW — and not without some controversy. Pre-acquisition, the startup was focused on democratizing access to research, behavior modification techniques and other tools that were previously only available through expensive programs run by hospitals or other centers.

As a WW product, however, there are concerns that parents putting kids on “diets” will lead to increased anxiety, stress and disordered eating — in other words, Kurbo will make the problem worse, rather than solving it.

The Kurbo app first launched at TechCrunch Disrupt NY 2014. Founder Joanna Strober, a venture investor and board member at BlueNile and eToys, explained she was driven to develop Kurbo after struggling to help her own child. Mainly, she came across programs that cost money, were held at inconvenient times for working parents or were dubbed “obesity centers” — with which no child wanted to be associated.

Her child found eventual success with the Stanford Pediatric Weight Loss Program, but this involved in-person visits and pen-and-paper documentation.

Together with Kurbo Health’s co-founder Thea Runyan, who has a Master’s in Public Health and had worked at the Stanford center for 12 years, the team realized the opportunity to bring the research to more people by creating a mobile, data-driven program for kids and families.

They licensed Stanford’s program, which then became Kurbo Health.

The company raised funds from investors, including Signia Ventures, Data Collective, Bessemer Venture Partners and Promus Ventures, as well as angels like Susan Wojcicki, CEO of YouTube; Greg Badros, former VP Engineering and Product at Facebook; and Esther Dyson (EdVenture), among others.

At launch, the app was designed to encourage healthier eating patterns without parents actually being able to see the child’s food diary. Instead, parents set a reward that was doled out simply for the child’s participation. That is, the parents couldn’t see what the child ate, specifically, which allowed them to stop playing “food police.”

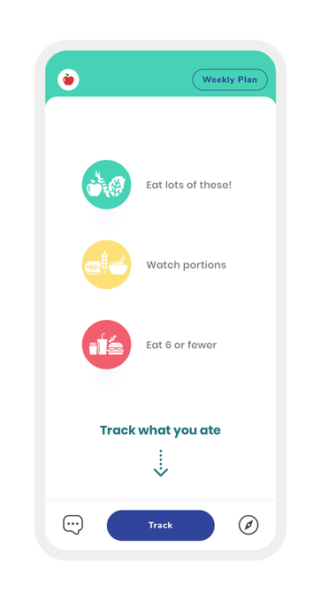

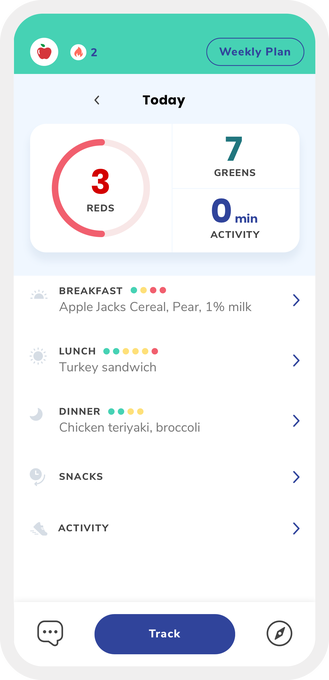

Unlike adult-oriented apps like MyFitnessPal or Noom, kids wouldn’t see metrics like calories, sugars, carbs and fat, but instead had their food choices categorized as “red,” “yellow” and “green.” However, no foods were designated as “off limits,” as it instead encouraged fewer reds and more greens.

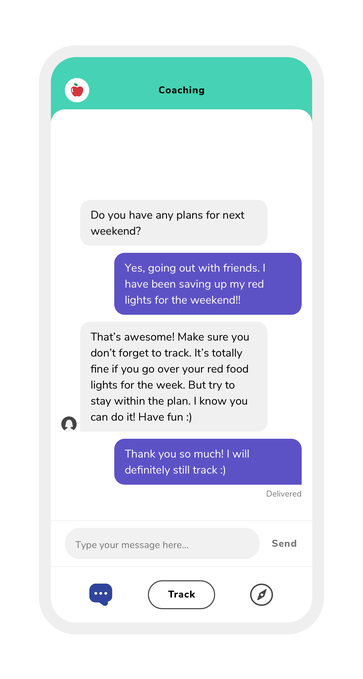

The program also included an option for virtual coaching.

As a WW product, the program has remained somewhat the same. There are still the color-coded food categorizations and optional live coaching, via a subscription. Parents are still involved, now with updates after coaching calls or the option to join coaching sessions. The app also now includes tools that teach meditation, recipe videos and games that focus on healthy lifestyles. Subscribers gain access to one-on-one 15-minute virtual sessions with coaches whose professional backgrounds include counseling, fitness and other nutrition-related fields.

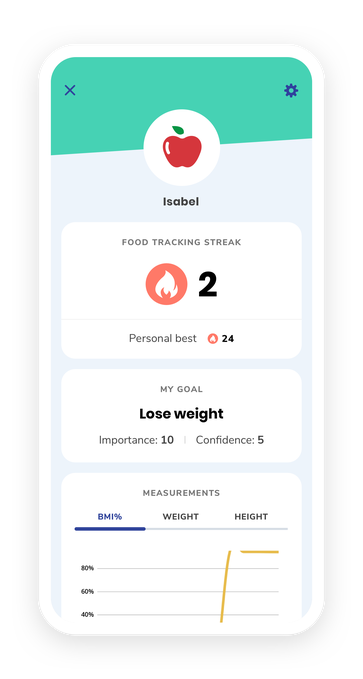

However, there are also things like a place to track measurements, goals like “lose weight” and Snapchat-style “tracking streaks.”

While the original program was designed to be a solution for parents with children who would have otherwise had to seek expensive medical help for obesity issues, the association with parent company and acquirer WW has led to some backlash.

Today, body positivity and fat acceptance movements have gone mainstream, encouraging people to be confident in their own bodies and not hate themselves for being overweight. The general thinking is that when people respect themselves, they become more likely to care for themselves — and this will extend to making healthier food and lifestyle choices.

Meanwhile, food tracking and dieting programs often lead to failure and shame — especially when people start to think of some food as “bad” or a “cheat,” instead of just something to be eaten in moderation. And excessive tracking can even lead to disordered eating patterns for some people, studies have found.

In addition, WW has already been under fire for extending its weight loss program to teens 13-17 for free, and the launch of what’s seen as a “dieting app for kids” as part of WW’s broader family-focused agenda certainly isn’t helping the backlash.

That said, when positive reinforcement is used correctly, it can work for weight loss. As TIME reported, the red-yellow-green traffic light approach was effective in adults in one independent study by Massachusetts General Hospital and another presented at the Biennial Childhood Obesity Conference worked in children, with 84% reducing their BMI after 21 weeks.

“According to recent reports from the World Health Organization, childhood obesity is one of the most serious public health challenges of the 21st century. This is a global public health crisis that needs to be addressed at scale,” said Joanna Strober, co-founder of Kurbo, in a statement about the launch. “As a mom whose son struggled with his weight at a young age, I can personally attest to the importance and significance of having a solution like Kurbo by WW, which is inherently designed to be simple, fun and effective,” she said.

That said, it’s one thing for a parent to work in conjunction with a doctor to help a child with a health issue, but parents who foist a food tracking app on their kids may not get the same results. In fact, they may even cause the child to develop eating disorders that weren’t present before. (And no, just because a child is overweight, that doesn’t necessarily mean they’re suffering from an “eating disorder.”)

There can be many other factors that could be causing a child’s unexpected weight gain, beyond just their interest in eating high-calorie foods. This includes health ailments, hormone or chemical imbalances, medication side effects, puberty and other growth spurts (which can’t always be determined through BMI changes, which are tracked in-app), genetics, and more.

Parents may also be part of the problem, by simply bringing unhealthy food into the house because it’s more affordable or because they aren’t aware of things like hidden sugars or how to avoid them. Or perhaps they’re putting money into a child’s school lunch account, without realizing the child is able to spend it on vending machine snacks, sodas or off-menu items like pizza and chips.

The child may also suffer from health problems like asthma or allergies that have become an underlying issue, making it more difficult for them to be active.

In other words, a program like this is something that parents should approach with caution. And it’s certainly one where the child’s doctor should be involved at every stage — including in determining whether or not an app is actually needed at all.